Show the code

Q = [1 1; 1 2]

r = [0, 1]

using LinearAlgebra

x_stationary = -Q\r

eigvals(Q)2-element Vector{Float64}:

0.38196601125010515

2.618033988749895We are going to analyze the optimization problem with no constraints \operatorname*{minimize}_{\bm x \in \mathbb{R}^n} \quad f(\bm x).

Why are we considering such an unrealistic problem? After all, every engineering problem is subject to some constraints.

Besides the standard teacher’s answer that we should always start with easier problems, there is another answer: it is common for analysis and algorithms for constrained optimization problems to reformulate them as unconstrained ones and then apply tools for unconstrained problems.

First, let’s define carefully what we mean by a minimum in the unconstrained problem.

For those whose mother tongue does not use articles such as the and a/an in English, it is worth emphasizing that there is a difference between “the minimum” and “a minimum”. In the former we assume that there is just one minimum, in the latter we make no such assumption.

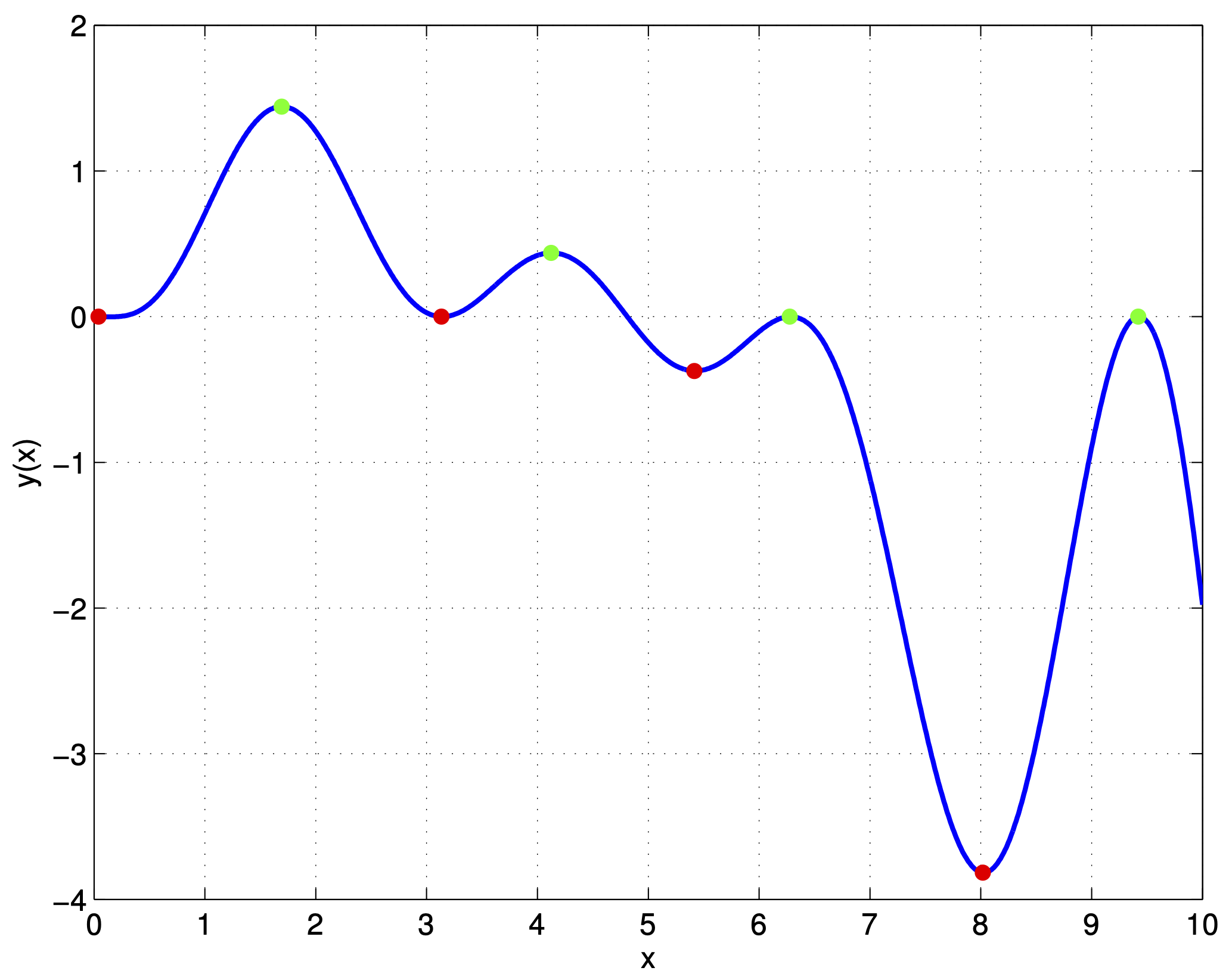

Consider a (scalar) function of a scalar variable for simplicity. Something like the function whose graph is shown in Fig. 1 below.

We say, that the function has a local minimum at x^\star if f(x)\geq f(x^\star) in an \varepsilon neighbourhood. All the red dots in the above figure are local minima. Similarly, of course, the function has a local maximum at x^\star if f(x)\leq f(x^\star) in an \varepsilon neighbourhood. Such local maxima are the green dots in the figure. The smallest and the largest of these are global minima and maxima, respectively.

Here we consider two types of conditions of optimality for unconstrained minimization problems: necessary and sufficient conditions. Necessary conditions must be satisfied at the minimum, but even when they are, the optimality is not guaranteed. On the other hand, the sufficient conditions need not be satisfied at the minimum, but if they are, the optimality is guaranteed. We show the necessary conditions of the first and second order, while the sufficient condition only of the second order.

You may want to have a look at the video, but below we continue with the text that covers (and polishes and sometimes even extends a bit) the content of the video.

We recall here the fundamental assumption made at the beginning of our introduction to optimization – we only consider optimization variables that are real-valued (first, just scalar x \in \mathbb R, later vectors \bm x \in \mathbb R^n), and objective functions f() that are sufficiently smooth – all the derivatives exist. Then the conditions of optimality can be derived upon inspecting the Taylor series approximation of the cost function around the minimum.

Denote x^\star as the (local) minimum of the function f(x). The Taylor series expansion of f(x) around x^\star is

f(x^\star+\alpha) = f(x^\star)+\left.\frac{\mathrm{d}f(x)}{\mathrm{d} x}\right|_{x=x^\star}\alpha + \frac{1}{2}\left.\frac{\mathrm{d^2}f(x)}{\mathrm{d} x^2}\right|_{x=x^\star}\alpha^2 + {\color{blue}\mathcal{O}(\alpha^3)}, where \mathcal{O}() is called Big O and has the property that \lim_{\alpha\rightarrow 0}\frac{\mathcal{O}(\alpha^3)}{\alpha^3} \leq M<\infty.

Alternatively, we can write the Taylor series expansion as f(x^\star+\alpha) = f(x^\star)+\left.\frac{\mathrm{d}f(x)}{\mathrm{d} x}\right|_{x=x^\star}\alpha + \frac{1}{2}\left.\frac{\mathrm{d^2}f(x)}{\mathrm{d} x^2}\right|_{x=x^\star}\alpha^2 + {\color{red}o(\alpha^2)}, using the little o with the property that \lim_{\alpha\rightarrow 0}\frac{o(\alpha^2)}{\alpha^2} = 0.

Whether \mathcal{O}() or \mathcal{o}() concepts are used, it is just a matter of personal preference. They both express that the higher-order terms in the expansion tend to be negligible compare to the first- and second-order term as \alpha is getting smaller. \mathcal O(\alpha^3) goes to zero at least as fast as a cubic function, while o(\alpha^2) goes to zero faster than a quadratic function.

It is indeed important to understand that this negligibility of the higher-order terms is only valid asymptotically – for a particular \alpha it may easily happend that, say, the third-order term is still dominating.

For \alpha sufficiently small, the first-order Taylor series expansion is a good approximation of the function f(x) around the minimum. Since \alpha enters this expansion linearly, the cost function can increase or decrease with \alpha, depending on the sign of the first derivative. The only way to ensure that the function as a (local) minimu at x^\star is to have the first derivative equal to zero, that is \boxed{ \left.\frac{\mathrm{d}f(x)}{\mathrm{d} x}\right|_{x=x^\star} = 0.}

Once the first-order necessary condition of optimality is satisfied, the dominating term (as \alpha is getting smalle) is the second-order term \frac{1}{2}\left.\frac{\mathrm{d^2}f(x)}{\mathrm{d} x^2}\right|_{x=x^\star}\alpha^2. Since \alpha is squared, it is the sign of the second derivative that determines the contribution of the whole second-order term to the cost function value. For the minimum, the second derivative must be nonnegative, that is

\boxed{\left.\frac{\mathrm{d^2}f(x)}{\mathrm{d} x^2}\right|_{x=x^\star} \geq 0.}

For completeness we state that the sign must be nonpositive for the maximum.

Following the same line of reasoning as above, the if the second derivative is positive, the miniumum is guaranteed, that is, the sufficient condition of optimality is \boxed{\left.\frac{\mathrm{d^2}f(x)}{\mathrm{d} x^2}\right|_{x=x^\star} > 0.}

If the second derivative fails to be positive and is just zero (thus still satisfying the necessary condition), does it mean that the point is not a minimum? No. We must examine higher order terms.

Once again, should you prefer watching a video, here it is, but below we continue with the text that covers the content of the video.

One way to handle the vector variables is to convert the vector problem into a scalar one by fixing a direction to an arbitrary vector \bm d and then considering the scalar function of the form f(\bm x^\star + \alpha \bm d). For convenience we define a new function g(\alpha) \coloneqq f(\bm x^\star + \alpha \bm d) and from now on we can invoke the results for scalar functions. Namely, we expand the g() function around zero as g(\alpha) = g(0) + \frac{\mathrm{d}g(\alpha)}{\mathrm{d}\alpha}\bigg|_{\alpha=0}\alpha + \frac{1}{2}\frac{\mathrm{d}^2 g(\alpha)}{\mathrm{d}\alpha^2}\bigg|_{\alpha=0}\alpha^2 + \mathcal{O}(\alpha^3), and argue that the first-order necessary condition of optimality is \frac{\mathrm{d}g(\alpha)}{\mathrm{d}\alpha}\bigg|_{\alpha=0} = 0.

Now, invoking the chain rule, we go back from g() to f() \frac{\mathrm{d}g(\alpha)}{\mathrm{d}\alpha}\bigg|_{\alpha=0} = \frac{\partial f(\bm x)}{\partial\bm x}\bigg|_{\bm x=\bm x^\star} \frac{\partial(\bm x^\star + \alpha \bm d)}{\partial\alpha}\bigg|_{\alpha=0} = \frac{\partial f(\bm x)}{\partial\bm x}\bigg|_{\bm x=\bm x^\star}\,\bm d = 0, where \frac{\partial f(\bm x)}{\partial\bm x}\bigg|_{\bm x=\bm x^\star} is a row vector of partial derivatives of f() evaluated at \bm x^\star. Since the vector \bm d is arbitrary, the necessary condition is that

\frac{\partial f(\bm x)}{\partial\bm x}\bigg|_{\bm x=\bm x^\star} = \mathbf 0,

More often than not we use the column vector to store partial derivatives. We call it the gradient of the function f() and denoted it as \nabla f(\bm x) \coloneqq \begin{bmatrix}\frac{\partial f(\bm x)}{\partial x_1} \\ \frac{\partial f(\bm x)}{\partial x_n} \\ \vdots \\ \frac{\partial f(\bm x)}{\partial x_n}\end{bmatrix}.

The first-order necessary condition of optimality using gradients is then \boxed{\left.\nabla f(\bm x)\right|_{x=x^\star} = \mathbf 0. }

In some literature the gradient \nabla f(\bm x) is defined as a row vector. For the condition of optimality it does not matteer since all we require is that all partial derivatives vanish. But for other purposes in our text we regard the gradient as a vector living in the same vector space \mathbb R^n as the optimization variable. The row vector is sometimes denoted as \mathrm Df(\bm x).

A convenient way is to compute the differential fist and then to identify the derivative in it. Recall that the differential is the first-order approximation to the increment of the function due to a change in the variable

\Delta f \approx \mathrm{d}f = \nabla f(x)^\top \mathrm d \bm x.

Finding the differential of a function is conceptually easier than finding the derivative since it is a scalar quantity. When searching for the differential of a composed function, we follow the same rules as for the derivative (such as that the one for finding the differential of a product). Let’s illustrate it using an example.

Example 1 For the function f(\mathbf x) = \frac{1}{2}\bm{x}^\top\mathbf{Q}\bm{x} + \mathbf{r}^\top\bm{x}, where \mathbf Q is symetric, the differential is \mathrm{d}f = \frac{1}{2}\mathrm d\bm{x}^\top\mathbf{Q}\bm{x} + \frac{1}{2}\bm{x}^\top\mathbf{Q}\mathrm d\bm{x} + \mathbf{r}^\top\mathrm{d}\bm{x}, in which the first two terms can be combined thanks to the fact that they are scalars \mathrm{d}f = \left(\bm{x}^\top\frac{\mathbf{Q} + \mathbf{Q}^\top}{2} + \mathbf{r}^\top\right)\mathrm{d}\bm{x}, and finally, since we assumed that \mathbf Q is a symmetric matrix, we get \mathrm{d}f = \left(\mathbf{Q}\bm{x} + \mathbf{r}\right)^\top\mathrm{d}\bm{x}, from which we can identify the gradient as \nabla f(\mathbf{x}) = \mathbf{Q}\mathbf{x} + \mathbf{r}.

The first-order condition of optimality is then \boxed{\mathbf{Q}\mathbf{x} = -\mathbf{r}.}

Although this was just an example, it is actually a very useful one. Keep this result in mind – necessary condition of optimality of a quadratic function comes in the form of a set of linear equations.

As before, we fix the direction \bm d and consider the function g(\alpha) = f(\bm x^\star + \alpha \bm d). We expand the expression for the first derivative as \frac{\mathrm d g(\alpha)}{\mathrm d \alpha} = \sum_{i=1}^{n}\frac{\partial f(\bm x)}{\partial x_i}\bigg|_{\bm x = \bm x^\star} d_i, and differentiating this once again, we get the second derivative \frac{\mathrm d^2 g(\alpha)}{\mathrm d \alpha^2} = \sum_{i,j=1}^{n}\frac{\partial^2 f(\bm x)}{\partial x_ix_j}\bigg|_{\bm x = \bm x^\star}d_id_j

\begin{aligned} \frac{\mathrm d^2 g(\alpha)}{\mathrm d \alpha^2}\bigg|_{\alpha=0} &= \sum_{i,j=1}^{n}\frac{\text{d}^2}{\text{d}x_ix_j}f(\bm x)\bigg|_{\bm x = \bm x^\star}d_id_j\\ &= \mathbf d^\text{T} \underbrace{\nabla^\text{2}f(\mathbf x)\bigg|_{\bm x = \bm x^\star}}_\text{Hessian} \mathbf d. \end{aligned} where \nabla^2 f(\mathbf x) is the Hessian (the symmetrix matrix of the second-order mixed partial derivatives) \nabla^2 f(x) = \begin{bmatrix} \frac{\partial^2 f(\mathbf x)}{\partial x_1^2} && \frac{\partial^2 f(\mathbf x)}{\partial x_1\partial x_2} && \ldots && \frac{\partial^2 f(\mathbf x)}{\partial x_1\partial x_n}\\ \frac{\partial^2 f(\mathbf x)}{\partial x_2\partial x_1} && \frac{\partial^2 f(\mathbf x)}{\partial x_2^2} && \ldots && \frac{\partial^2 f(\mathbf x)}{\partial x_2\partial x_n}\\ \vdots\\ \frac{\partial^2 f(\mathbf x)}{\partial x_n\partial x_1} && \frac{\partial^2 f(\mathbf x)}{\partial x_n\partial x_2} && \ldots && \frac{\partial^2 f(\mathbf x)}{\partial x_n\partial x_n}. \end{bmatrix}

Since \bm d is arbitrary, the second-order necessary condition of optimality is then \boxed{\nabla^\text{2}f(\mathbf x)\bigg|_{\bm x = \bm x^\star} \succeq 0,} where, once again, the inequality \succeq reads that the matrix is positive semidefinite.

\boxed{\nabla^2 f(\mathbf x)\bigg|_{\bm x = \bm x^\star} \succ 0,} where, once again, the inequality \succ reads that the matrix is positive definite.

Example 2 For the quadratic function f(\mathbf x) = \frac{1}{2}\mathbf{x}^\mathrm{T}\mathbf{Q}\mathbf{x} + \mathbf{r}^\mathrm{T}\mathbf{x}, the Hessian is \nabla^2 f(\mathbf{x}) = \mathbf{Q} and the second-order necessary condition of optimality is \boxed{\mathbf{Q} \succeq 0.}

Second-order sufficient condition of optimality is then \boxed{\mathbf{Q} \succ 0.}

Once again, this was more than just an example – quadratic functions are so important for us that it is worth remembering this result.

For a stationary (also critical) point \bm x^\star, that is, one that satisfies the first-order necessary condition \nabla f(\bm x^\star) = 0,

we can classify it as

Example 3 (Minimum of a quadratic function) We consider a quadratic function f(\mathbf x) = \frac{1}{2}\mathbf{x}^\mathrm{T}\mathbf{Q}\mathbf{x} + \mathbf{r}^\mathrm{T}\mathbf{x} for a particular \mathbf{Q} and \mathbf{r}.

Q = [1 1; 1 2]

r = [0, 1]

using LinearAlgebra

x_stationary = -Q\r

eigvals(Q)2-element Vector{Float64}:

0.38196601125010515

2.618033988749895The matrix is positive definite, so the stationary point is a minimum. In fact, the minimum. Surface and contour plots of the function are shown below.

f(x) = 1/2*dot(x,Q*x)+dot(x,r)

x1_data = x2_data = -4:0.1:4;

f_data = [f([x1,x2]) for x2=x2_data, x1=x1_data];

using Plots

display(surface(x1_data,x2_data,f_data))

contour(x1_data,x2_data,f_data)

display(plot!([x_stationary[1]], [x_stationary[2]], marker=:circle, label="Stationary point"))GKS: cannot open display - headless operation mode activeExample 4 (Saddle point of a quadratic function)

Q = [-1 1; 1 2]

r = [0, 1]

using LinearAlgebra

x_stationary = -Q\r

eigvals(Q)2-element Vector{Float64}:

-1.3027756377319946

2.302775637731995The matrix is indefinite, so the stationary point is a saddle point. Surface and contour plots of the function are shown below.

f(x) = 1/2*dot(x,Q*x)+dot(x,r)

x1_data = x2_data = -4:0.1:4;

f_data = [f([x1,x2]) for x2=x2_data, x1=x1_data];

using Plots

display(surface(x1_data,x2_data,f_data))

contour(x1_data,x2_data,f_data)

display(plot!([x_stationary[1]], [x_stationary[2]], marker=:circle, label="Stationary point"))Example 5 (Singular point of a quadratic function)

Q = [2 0; 0 0]

r = [3, 0]

using LinearAlgebra

eigvals(Q)2-element Vector{Float64}:

0.0

2.0The matrix Q is singular, which has two consequences:

Q is not invertible. In fact, there is a whole line (a subspace) of stationary points.Q is positive semidefinite, which generally means that optimality cannot be concluded. But in this particular case of a quadratic function, there are no higher-order terms in the Taylor series expansion, so the stationary point is a minimum.Surface and contour plots of the function are shown below.

f(x) = 1/2*dot(x,Q*x)+dot(x,r)

x1_data = x2_data = -4:0.1:4;

f_data = [f([x1,x2]) for x2=x2_data, x1=x1_data];

using Plots

display(surface(x1_data,x2_data,f_data))

display(contour(x1_data,x2_data,f_data))Example 6 (Singular point of a non-quadratic function) Consider the function f(\bm x) = x_1^2 + x_2^4. Its gradient is \nabla f(\bm x) = \begin{bmatrix}2x_1\\ 4x_2^3\end{bmatrix} and it vanishes at \bm x^\star = \begin{bmatrix}0\\ 0\end{bmatrix}. The Hessian is \nabla^2 f(\bm x) = \begin{bmatrix}2 & 0\\ 0 & 12x_2^2\end{bmatrix}, which when evaluated at the stationary point is \nabla^2 f(\bm x)\bigg|_{\bm x=\mathbf 0} = \begin{bmatrix}2 & 0\\ 0 & 0\end{bmatrix}, which is positive semidefinite. We cannot conclude if the function attains a minimum at \bm x^\star.

We need to examine higher-order terms in the Taylor series expansion. The third derivatives are \frac{\partial^3 f}{\partial x_1^3} = 0, \quad \frac{\partial^3 f}{\partial x_1^2\partial x_2} = 0, \quad \frac{\partial^3 f}{\partial x_1\partial x_2^2} = 0, \quad \frac{\partial^3 f}{\partial x_2^3} = 24x_2, and when evaluated at zero, they all vanish.

All but one fourth derivatives also vanish. The one that does not is \frac{\partial^4 f}{\partial x_2^4} = 24, which is positive, and since the associated derivative is of the even order, the power si also even, hence the function attains a minimum at \bm x^\star = \begin{bmatrix}0\\ 0\end{bmatrix}.

This can also be visually confirmed by the surface and contour plots of the function.

f(x) = x[1]^2 + x[2]^4

x1_data = x2_data = -4:0.1:4;

f_data = [f([x1,x2]) for x2=x2_data, x1=x1_data];

using Plots

display(surface(x1_data,x2_data,f_data))

contour(x1_data,x2_data,f_data)

display(plot!([0.0], [0.0], marker=:circle, label="Stationary point"))