Optimization problems

Optimization problem formulation

We formulate a general optimization problem (also a mathematical program) as \begin{aligned} \operatorname*{minimize} \quad & f(\bm x) \\ \text{subject to} \quad & \bm x \in \mathcal{X}, \end{aligned} where f is a scalar function, \bm x can be a scalar, a vector, a matrix or perhaps even a variable of yet another type, and \mathcal{X} is a set of values that \bm x can take, also called the feasible set.

The term “program” here has nothing to do with a computer program. Instead, it was used by the US military during the WWII to refer to plans or schedules in training and logistics.

If maximization of the objective function f() is desired, we can simply multiply the objective function by -1 and minimize the resulting function.

Typically there are two types of constraints that can be imposed on the optimization variable \bm x:

- explicit characterization of the set such as \bm x \in \mathbb{R}^n or \bm x \in \mathbb{Z}^n, possibly even a direct enumeration such as \bm x \in \{0,1\}^n in the case of binary variables,

- implicit characterization of the set using equations and inequalities such as g_i(\bm x) \leq 0 and h_i(\bm x) = 0 for i = 1, \ldots, m and j = 1, \ldots, p.

An example of a more structured and yet sufficiently general optimization problems over several real and integer variables is \begin{aligned} \operatorname*{minimize}_{\bm x \in \mathbb{R}^{n_x}, \, \bm y \in \mathbb{Z}^{n_y}} \quad & f(\bm x, \bm y) \\ \text{subject to} \quad & g_i(\bm x, \bm y) \leq 0, \quad i = 1, \ldots, m, \\ & h_j(\bm x, \bm y) = 0, \quad j = 1, \ldots, p. \end{aligned}

Indeed, for named sets such as \mathbb R or \mathbb Z, it is common to place the set constraints directly underneath the word “minimize”. But it is just one convention, and these constraints could be listed in the “subject to” section as well.

In this course we are only going to consider optimization problems with real-valued variables. This decision does not suggest that optimization with integer variables is less relevant for optimal control, quite the opposite! It is just that the theory and algorithms for integer or mixed integer optimization are based on different principles than those for real variables. And they can hardly fit into a single course. Good news for the interested students is that a graduate course named Combinatorial algorithms (B3B35KOA) covering integer optimization in detail is offered by our Cybernetics and Robotics study program at CTU FEE. Additionally, applications of integer optimization to optimal control are partly discussed in the course on Hybrid systems (B3B39HYS).

The form of an optimization problem that we are going to use in our course most often than not is \begin{aligned} \operatorname*{minimize}_{\bm x \in \mathbb{R}^n} \quad & f(\bm x) \\ \text{subject to} \quad & g_i(\bm x) \leq 0, \quad i = 1, \ldots, m, \\ & h_i(\bm x) = 0, \quad i = 1, \ldots, p, \end{aligned} which can also be written using vector-valued functions (reflected in the use of the bold face for their names) \begin{aligned} \operatorname*{minimize}_{\bm x \in \mathbb{R}^n} \quad & f(\bm x) \\ \text{subject to} \quad & \mathbf g(\bm x) \leq 0,\\ & \mathbf h(\bm x) = 0. \end{aligned}

Properties of optimization problems

It is now the presence/absence and the properties of individual components in the optimization problem defined above that characterize classes of optimization problems. In particular, we can identify the following properties:

- Unconstrained vs constrained

- Practically relevant problems are almost always constrained. But still there are good reasons to study unconstrained problems too, as many theoretical results and algorithms for constrained problems are based on transformations to unconstrained problems.

- Linear vs nonlinear

- By linear problems we mean problems where the objective function and all the functions defining the constraints are linear (or actually affine) functions of the optimization variable \bm x. Such problems constitute the simplest class of optimization problems, are very well understood, and there are efficient algorithms for solving them. In contrast, nonlinear problems are typically more difficult to solve (but see the discussion of the role of convexity below).

- Smooth vs nonsmooth

- Efficient algorithms for optimization over real variables benefit heavily from knowledge of the derivatives of the objective and constraint functions. If the functions are differentiable (aka smooth), we say that the whole optimization problem is smooth. Nonsmooth problems are typically more difficult to analyze and solve (but again, see the discussion of the role of convexity below).

- Convex vs nonconvex

- If the objective function and the feasible set are convex (the latter holds when the functions defining the inequality constraints are convex and the functions defining the equality constrains are affine), the whole optimization problem is convex. Convex optimization problems are very well understood and there are efficient algorithms for solving them. In contrast, nonconvex problems are typically more difficult to solve. It is not becomming a common knowledge that convexity is a lot more important property than linearity and smoothness when it comes to solving optimization problems efficiently.

Classes of optimization problems

Based on the properties discussed above, we can identify the following distinct classes of optimization problems:

Linear program (LP)

\begin{aligned} \operatorname*{minimize}_{\bm x \in \mathbb{R}^n} \quad & \mathbf c^\top \bm x \\ \text{subject to} \quad & \mathbf A_\mathrm{ineq}\bm x \leq \mathbf b_\mathrm{ineq},\\ & \mathbf A_\mathrm{eq}\bm x = \mathbf b_\mathrm{eq}. \end{aligned}

An LP is obviously linear, hence it is also smooth and convex.

Some theoretical results and numerical algorithms require a linear program in a specific form, called the standard form: \begin{aligned} \operatorname*{minimize}_{\bm x \in \mathbb{R}^n} \quad & \mathbf c^\top \bm x \\ \text{subject to} \quad & \mathbf A\bm x = \mathbf b,\\ & \bm x \geq \mathbf 0, \end{aligned} where the inequality \bm x \geq \mathbf 0 is understood componentwise, that is, x_i \geq 0 for all i = 1, \ldots, n.

Quadratic program (QP)

\begin{aligned} \operatorname*{minimize}_{\bm x \in \mathbb{R}^n} \quad & \bm x^\top \mathbf Q \bm x + \mathbf c^\top \bm x \\ \text{subject to} \quad & \mathbf A_\mathrm{ineq}\bm x \leq \mathbf b_\mathrm{ineq},\\ & \mathbf A_\mathrm{eq}\bm x = \mathbf b_\mathrm{eq}. \end{aligned}

Even though the QP is nonlinear, it is smooth and if the matrix \mathbf Q is positive semidefinite, it is convex. Its analysis and numerical solution are not much more difficult than those of an LP problem.

Quadratically constrained quadratic program (QCQP)

It is worth emphasizing that for the standard QP the constraints are still given by a system of linear equations and inequalities. Sometimes we can encounter problems in which not only the cost function but also the functions defining the constraints are quadratic as in \begin{aligned} \operatorname*{minimize}_{\bm x \in \mathbb{R}^n} \quad & \bm x^\top \mathbf Q \bm x + \mathbf c^\top \bm x \\ \text{subject to} \quad & \bm x^\top \mathbf A_i\bm x + \mathbf b_i \bm x + c_i \leq \mathbf 0, \quad i=1, \ldots, m. \end{aligned}

A QCQP problem is convex if and only if the the constraints define a convex feasible set, which is the case when all the matrices \mathbf A_i are positive semidefinite.

Conic program (CP)

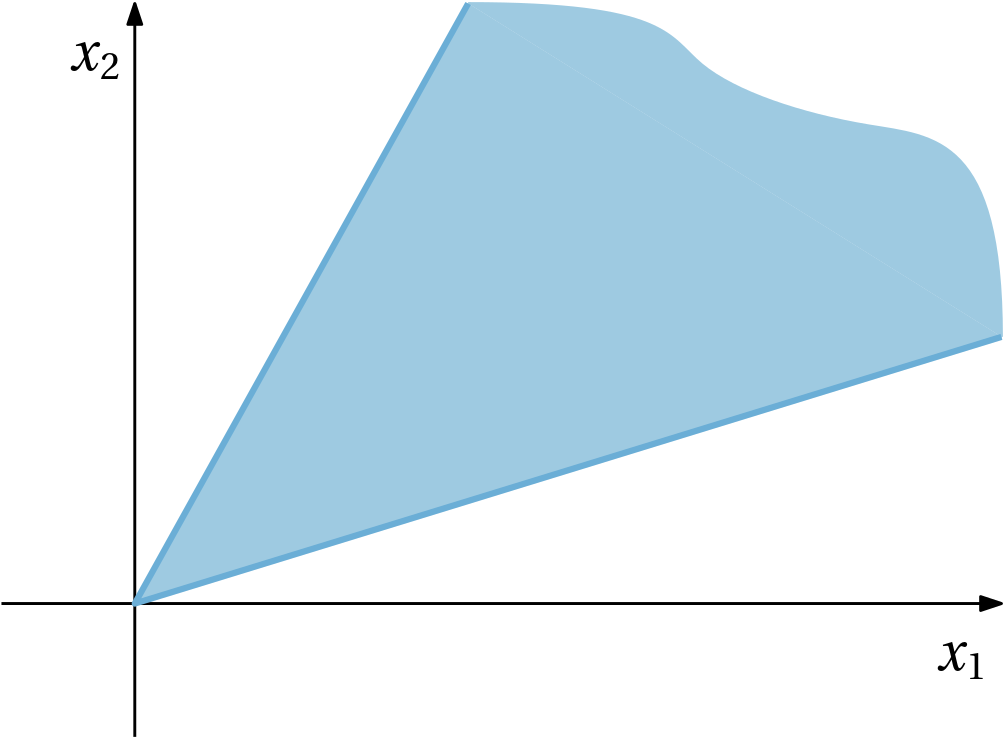

First, what is a cone? It is a set such that if something is in the cone, then a multiple of it by a nonnegative number is still in the set. We are going to restrict ourselves to regular cones, which are are pointed, closed and convex. An example of such regular cone in a plane is in Fig. 1 below.

Now, what is the role of cones in optimization? Reformulation of nonlinear optimization problems using cones constitutes a systematic way to identify what these (conic) optimization problems have in common with linear programs, for which powerful theory and efficient algorithms exist.

Note that an LP in the standard form can be written as \begin{aligned} \operatorname*{minimize} &\quad \mathbf c^\top \bm x\\ \text{subject to} &\quad \mathbf A\bm x = \mathbf b,\\ &\quad \bm x\in \mathbb{R}_+^n, \end{aligned} where \mathbb R_+^n is a positive orthant. Now, the positive orthant is a convex cone! We can then see the LP as an instance of a general conic optimization problem (conic program)

\begin{aligned} \operatorname*{minimize} &\quad \mathbf c^\top \bm x\\ \text{subject to} &\quad \mathbf A\bm x = \mathbf b,\\ &\quad \bm x\in \mathcal{K}, \end{aligned} where \mathcal{K} is a cone in \mathbb R^n.

A fundamental idea unrolled here: the inequality \bm x\geq 0 can be interpreted as \bm x belonging to a componentwise nonegative cone, that is \bm x \in \mathbb R_+^n. What if some other cone \mathcal K is considered? What would be the interpretation of the inequality then?

Sometimes in order to emphasize that the inequality is induced by the cone \mathcal K, we write it as \geq_\mathcal{K}. Another convention – the one we actually adopt here – is to use another symbol for the inequality \succeq to distinguish it from the componentwise meaning, assuming that the cone is understood from the context. We then interpret conic inequalities such as \mathbf A_\mathrm{ineq}\bm x \succeq \mathbf b_\mathrm{ineq} in the sense that \mathbf A_\mathrm{ineq}\bm x - \mathbf b_\mathrm{ineq} \in \mathcal{K}.

It is high time to explore some concrete cones (other than the positive orthant). We consider just two, but there are a few more, see the literature.

Second-order cone program (SOCP)

The most immediate cone in \mathbb R^n is the second-order cone, also called the Lorentz cone or even the ice cream cone. We explain it in \mathbb R^3 for the ease of visualization, but generalization to \mathbb R^n is straightforward. The second-order cone in \mathbb R^3 is defined as \mathcal{K}_\mathrm{SOC}^3 = \left\{ \bm x \in \mathbb R^3 \mid \sqrt{x_1^2 + x_2^2} \leq x_3 \right\}.

and is visualized in Fig. 2 below.

Which of the three axes plays the role of the axis of symmetry for the cone must be agreed beforehand. Singling this direction out, the SOC in \mathbb R^n can also be formulated as \mathcal{K}_\mathrm{SOC}^n = \left\{ (\bm x, t) \in \mathbb R^{n-1} \times \mathbb R \mid \|\bm x\|_2 \leq t \right\}.

A second-order conic program in standard form is then \begin{aligned} \operatorname*{minimize} &\quad \mathbf c^\top \bm x\\ \text{subject to} &\quad \mathbf A\bm x = \mathbf b,\\ &\quad \bm x\in \mathcal{K}_\mathrm{SOC}^n, \end{aligned}

which can be written explicitly as \begin{aligned} \operatorname*{minimize} &\quad \mathbf c^\top \bm x\\ \text{subject to} &\quad \mathbf A\bm x = \mathbf b,\\ &\quad x_1^2 + \cdots + x_{n-1}^2 - x_n^2 \leq 0. \end{aligned}

A second-order conic program can also come in non-standard form such as \begin{aligned} \operatorname*{minimize} &\quad \mathbf c^\top \bm x\\ \text{subject to} &\quad \mathbf A_\mathrm{ineq}\bm x \succeq \mathbf b_\mathrm{ineq}. \end{aligned}

Assuming the data is structured as \begin{bmatrix} \mathbf A\\ \mathbf r^\top \end{bmatrix} \bm x \succeq \begin{bmatrix} \mathbf b\\ q \end{bmatrix}, the inequality can be rewritten as \begin{bmatrix} \mathbf A\\ \mathbf r^\top \end{bmatrix} \bm x - \begin{bmatrix} \mathbf b\\ q \end{bmatrix} \in \mathcal{K}_\mathrm{SOC}^n, which finally gives \|\mathbf A \bm x - \mathbf b\|_2 \leq \mathbf r^\top \bm x + q.

To summarize, another form of a second-order cone program (SOCP) is

\begin{aligned} \operatorname*{minimize} &\quad \mathbf c^\top \bm x\\ \text{subject to} &\quad \mathbf A_\mathrm{eq}\bm x = \mathbf b_\mathrm{eq},\\ &\quad \|\mathbf A \bm x - \mathbf b\|_2 \leq \mathbf r^\top \bm x + q. \end{aligned}

We can see that the SOCP contains both linear and quadratic constraints, hence it generalizes LP and QP, including convex QCQP. To see the latter, expand the square of \|\mathbf A \bm x - \mathbf b\|_2 into (\bm x^\top \mathbf A^\top - \mathbf b^\top)(\mathbf A \bm x - \mathbf b) = \bm x^\top \mathbf A^\top \mathbf A \bm x + \ldots

Semidefinite program (SDP)

Another cone of great importance the control theory is the cone of positive semidefinite matrices. It is commonly denoted as \mathcal S_+^n and is defined as \mathcal S_+^n = \left\{ \bm X \in \mathbb R^{n \times n} \mid \bm X = \bm X^\top, \, \bm z^\top \bm X \bm z \geq 0\; \forall \bm z\in \mathbb R^n \right\}, and with this cone the inequality \mathbf X \succeq 0 is a common way to express that \mathbf X is positive semidefinite.

Unlike the previous classes of optimization problems, this one is formulated with matrix variables instead of vector ones. But nothing prevents us from collecting the components of a symmetric matrix into a vector and proceed with vectors as usual, if needed:

\bm X = \begin{bmatrix} x_1 & x_2 & x_3 \\ x_2 & x_4 & x_5\\ x_3 & x_5 & x_6 \end{bmatrix}, \quad \bm x = \begin{bmatrix} x_1 \\ x_2 \\ \vdots \\ x_6 \end{bmatrix}.

An optimization problem with matrix variables constrained to be in the cone of semidefinite matrices (or their vector representations) is called a semidefinite program (SDP). As usual, we start with the standard form, in which the cost function is linear and the optimization is subject to an affine constraint and a conic constraint. In the following, in place of the inner products of two vectors \mathbf c^\top x we are going to use inner products of matrices defined as \langle \mathbf C, \bm X\rangle = \operatorname{Tr} \mathbf C \bm X, where \operatorname{Tr} is a trace of a matrix defined as the sum of the diagonal elements.

The SDP program in the standard form is then \begin{aligned} \operatorname{minimize}_{\bm X} &\quad \operatorname{Tr} \mathbf C \bm X\\ \text{subject to} &\quad \operatorname{Tr} \mathbf A_i \bm X = \mathbf b_i, \quad i=1, \ldots, m,\\ &\quad \bm X \in \mathcal S_+^n, \end{aligned} where the latter constraint is more often than not written as \bm X \succeq 0, understanding from the context that the cone of positive definite matrices is assumed.

Other conic programs

We are not going to cover them here, but we only enumerate a few other cones useful in optimization: rotated second-order cone, exponential cone, power cone, … A concise overview is in [1]

Geometric program (GP)

#TODO: although of little immediate use in our course.

Nonlinear program (NLP)

For completeness we include here once again the general nonlinear programming problem:

\begin{aligned} \operatorname*{minimize}_{\bm x \in \mathbb{R}^n} \quad & f(\bm x) \\ \text{subject to} \quad & \mathbf g(\bm x) \leq 0,\\ & \mathbf h(\bm x) = 0. \end{aligned}

Smoothness of the problem can easily be determined based on the differentiability of the functions. Convexity can also be determined by inspecting the functions, but this is not necessarily easy. One way to check convexity of a function is to view it as a composition of simple functions and exploit the knowledge about convexity of these simple functions. See [2, Sec. 3.2]