Calculus of variations

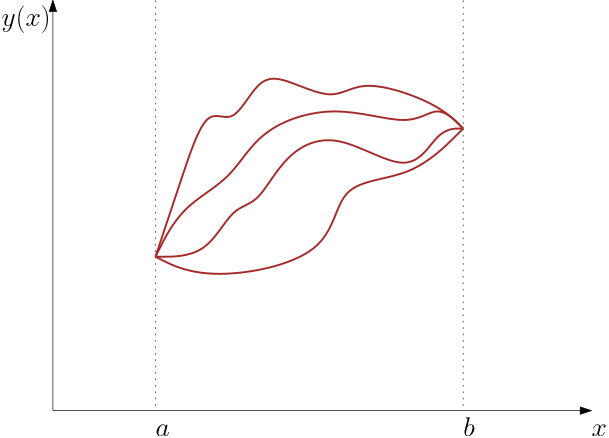

Since in our quest for the optimal control we optimize over functions (trajectories), we can view our optimization as cast in an infinite-dimensional vector space. The mathematical discipline of calculus of variations provides concepts and tools for such optimization. The general task (in a scalar version) is to find

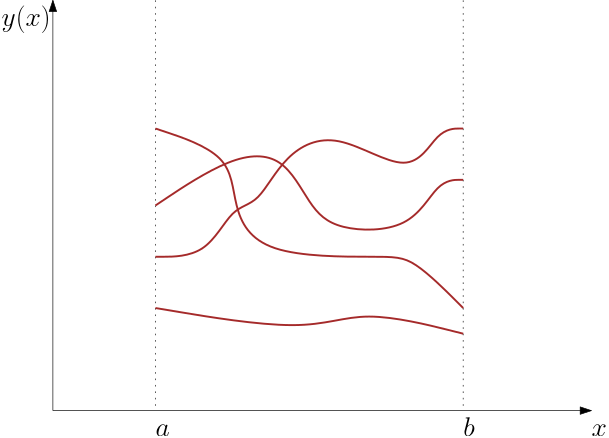

\min_{y(x)\in\mathcal C^1[a,b]} J(y(x)), where we relabelled the variables in the following sense: the optimization is performed over functions y(\cdot), which are functions of the independent scalar variable x. The reason for this notational choice is that many of the results in calculus of variations were motivated by problems where the independent variable was length or position. This change of notation is reflected in Fig. 1, which shows a few members of the space in which we search for a minimizer.

Having specified the optimization variable, we need to talk about the cost function. It is now a function of a function. An established name for such functions is functional.

Just minor warning about the usage of the concept of a functional in mathematics. While it is generally understood as a function that assigns a real (or complex) number to its argument, the arguments can be an element of any vectors space, not just a space of functions. But the established usage within the discipline of calculus of variations is that the argument is in a set of functions (for instance, \mathcal C^1[a,b], the set of of continuously differentiable functions).

It is now important to reinvoke the very definition of local minimum that we introduced in the lecture on finite-dimensional optimization. The cost function has a local minimum at a given point if there exists some neighbourhood within which all the other points achieve equal or higher value. With our current notation, J attains a local minimum at y^\star if J(y^\star) \leq J(y) for all y in some neighbourhood of y^\star. The neighbourhood is given as a set of all those y for which \|y-y^\star\| \leq \epsilon.

Strong vs. weak minimum

The question is, which norm is used in the expression above. In finite-dimensional spaces the choice of a norm did not have an impact on whether a given point was classified as a minimum or not. We could use 2-norm (the popular Euclidean norm), 1-norm (also called Manhattan norm) or \infty-norm (also called max norm). But the situation is dramatically different in infinite dimensional vector spaces; and the spaces of function can be viewed as having an infinite dimension. Restricting ourselves to the space \mathcal{C}^1 of continuously differentiable functions, there are two main norms that are popular in calculus of variations. First, the so-called 0-norm, which is defined as \|y\|_0=\max_{x\in [a,b]} |y(x)|.

The second type of norm that we will use is called 1-norm

\|y\|_1=\max_{x\in [a,b]} |y(x)| + \max_{x\in [a,b]} |y'(x)|.

Admittedly, the notation might be (again) a bit confusing as \|.\|_1 is typically used for the sum-of-absolute-values and integral-of-absolute-values norms used elsewhere. But that’s how it is… Different disciplines adopted different conventions. Similarly, the definition of \|.\|_0 resembles the one of the \infty-norm (also sup-norm) used elsewhere, but while the former is restricted to smooth functions, the latter is used for a broader family of functions – essentially bounded measurable function, also denoted as \mathcal L_\infty.

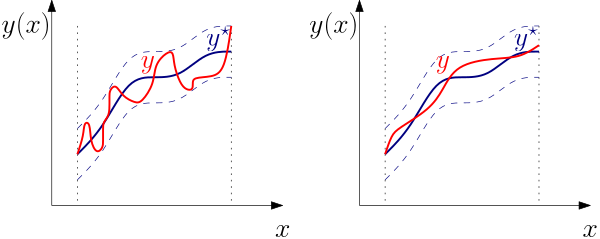

When \|.\|_0 norm is used to define the neighbourhood, we say that J attains a strong minimum at y^\star. When \|.\|_1 norm is used instead, the attained minimum is weak.

It may take a few seconds to realize that if y^\star is a strong minimum, it is automatically weak. The oposite is not true. If y^\star is a weak minimum, it is not necessarily strong. In other words, for a fixed \varepsilon, the set N_1=\{y:\|y-y^\star\|_0\leq \varepsilon\} contains all the members of the set N_2=\{y:\|y-y^\star\|_1\leq \varepsilon\} but the other direction does not hold. The visualization in Fig. 2 may help see this.

Example 1 Consider the minimization of the functional J(y)=\int_\mathrm{i}^1[(y'(x))^2(1-(y'(x))^2)]\text{d}x for which it is requested that y(a)=y(b)=0. Clearly y(x)=0 is a weak minimum but is not a strong minimum. Just observe that even for tiny perturbations in magnitude, if the derivative is high, that is, (y'(x))^2>1, the functional J is negative.

What is the role of these two norms in our course? The former—the \|.\|_0 norm—and the related concept of strong minimum are what we would like to test for, while the latter—the \|.\|_1 norm—and the related concept of weak minimum are just mathematically more convenient. It is much easier to show that a point is a weak minimum. Nonetheless, the distinction between these two will only be relevant once we want to find sufficient conditions of optimality, and we are not there yet. First we need to find the (first-order) necessary conditions of optimality.

Variation, variational derivative and first-order conditions of optimality

Similarly as in the finite-dimensional optimization, we will build the necessary conditions of optimality by studying how the cost function changes if we perturb the independent variable a bit. Let’s denote the minimizing function as y^\star. We denote the perturbed function as y and we form it as y(x) = y^\star(x) + \delta y(x), where \delta y(\cdot) is variation of function and it is a function itself. It plays the same role in calculus of variations as the term \mathrm{d}x does in differential calculus.

Recall that one aproach to deriving the first-order necessary conditions of optimality in the case of vector variables was based on fixing the direction first and then analyzing how the function evolves along this direction. Namely, we considered evolution of the cost function f(\mathbf x^\star + \alpha\, \mathbf d) \tag{1} for given \mathbf x^\star\in\mathbb{R}^n and \mathbf d\in\mathbb{R}^n while varying \alpha\in\mathbb{R}. This enabled us to convert the vector problem into a scalar one. We can follow this procedure while perturbing a function. Namely, we can build the variation of a function by writing it as \delta y(x) = \alpha \eta(x), \tag{2} where \eta(x) is a given (but arbitrary) function in \mathcal{C}^1 (playing the role of \mathbf d in the finite-dimensional optimization) and \alpha\in\mathbb R. This way we are about to convert optimization over functions to optimization over real numbers.

Before we proceed, let’s elaborate a bit more on the above expression. Let’s assume that the function y(x) in the neighbourhood of the minimizing function y^\star(x) is actually parameterized by some real parameter \alpha, and that for \alpha=0 it becomes the minimizing function y^\star(x). The Taylor expansion around \alpha = 0 is y(x,\alpha) = \underbrace{y(x,0)}_{y^\star(x)} + \left.\frac{\partial y(x,\alpha)}{\partial \alpha}\right|_{\alpha=0} \alpha + \mathcal{O}(\alpha^2).

The second term on the right is then the variation \delta y of the function y. We will write it down here for later reference \delta y(x) = \underbrace{\left.\frac{\partial y(x,\alpha)}{\partial \alpha}\right|_{\alpha=0}}_{\eta(x)} \alpha. \tag{3}

This add an interpretation to Eq. 2. Note also that for a fixed x, the variation is just a differential with respect to \alpha (recall that a differential is the first-order approximation to the increment).

So far, so good. We have now discussed in quite some detail the concept of variation of a function, that is, the concept that will be used to describe the perturbation of the input argument of a cost functional. But now we want to see if another analogy can be found with the differential calculus. Recall that the first-order necessary condition of optimality of a cost function f(x) of a scalar real argument x is that the differential of the cost function vanishes, that is, \mathrm d f = 0.

But we also know that that the differential is defined as the first-order approximation to the increment in the input argument, that is \mathrm d f = \underbrace{f'}_{\frac{\mathrm d f}{\mathrm d x} } \mathrm d x=0, from which it follows that if the variable x is unconstrained, the first-order condition of optimality can be given as a condition on the derivative f'(x) = 0.

In case of a vector variables \mathbf x\in\mathbb R^n, we rewrite the above condition on the differential as \mathrm d f = (\nabla f)^\mathrm{T}\, \mathbf{d}\mathbf{x} = 0, \tag{4} from which it follows that \nabla f = \mathbf 0.

Having recapitulated these basic facts from differential calculus, we are now curious if we can do similar development within calculus of variations. Namely, we would like to express the variation of the cost functional using the variation of the function, thus mimicking Eq. 4. Note that the product in Eq. 4 is actually the inner product (some may even write it as \mathrm d f = \langle \nabla f, \mathbf{d}\mathbf{x} \rangle). And inner products are also defined in other vector spaces, not just Euclidean spaces of n-tuples. For continuous functions, they are defined using integrals instead of sums. Namely, we have \boxed{ \delta J = \int_a^b {\color{red}\frac{\delta J}{\delta y(x)}} \, \delta y(x)\mathrm d x, } where the fraction in the above expression is called variational derivative.

The whole fraction should be regarded just as one symbol. You should not really treat it as a true ratio (and cancel the denominator term with the other \delta y term). This is the same type of a trap that you can encounter in differential calculus using Leibniz’s notation.

Now, following Eq. 3, we may want to express the variation of J as \delta J = \left.\frac{\mathrm{d} J}{\mathrm{d} \alpha}\right|_{\alpha=0}\alpha. \tag{5}

We compute the derivative of the cost with respect to the real parameter \alpha first (recall that both the y and the \eta functions are considered as fixed here) \left.\frac{\mathrm{d}}{\mathrm{d} \alpha}J(y(x)+\alpha\eta(x))\right|_{\alpha=0} = \lim_{\alpha\rightarrow 0}\frac{J(y(x)+\alpha\eta(x))-J(y(x))}{\alpha}, \tag{6} and once we have it, we just multiply the result by \alpha, and we have the desired variation of the cost.

We are not going to consider completely arbitrary cost function(al)s, instead we are only going to consider a useful subset. We start by considering some concrete examples. We will then extract some common features and characterize some general and yet narrow enough family of cost functionals.

Some examples of calculus of variations

Minimum distance between two points

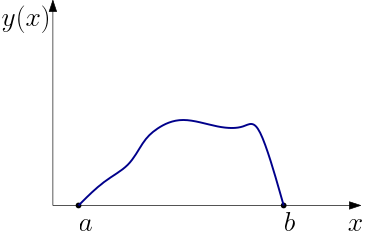

Consider two points in the plane. The task is to find the curve that connects these two points and minimizes the total length. Without a loss of generality, we consider the two ends on the x-axis as in Fig. 3. Although the answer to this problem is trivial, the problem serves a good job of demonstrating the essence of calculus of variations.

The total length of the curve is J(y) = \int_a^b \sqrt{(\mathrm d x)^2+(\mathrm d y)^2}= \int_a^b \sqrt{1+(y'(x))^2}\text{d}x. The optimization problem is then \operatorname*{minimize}_{y\in\mathcal{C}^1_{[a,b]}} \int_a^b \sqrt{1+(y'(x))^2}\text{d}x.

Dido’s problem

Given a rope of length c, what is the maximum area this rope can circumscribe? Obviously, here we have a problem with an equality-type constraint \begin{aligned} \operatorname*{minimize}_{y\in\mathcal{C}^1_{[a,b]}} &\quad \int_a^b y(x)\text{d}x,\\ \text{subject to} &\quad \int_a^b \sqrt{1+(y'(x))^2}\text{d}x = c. \end{aligned}

Brachistochrone problem

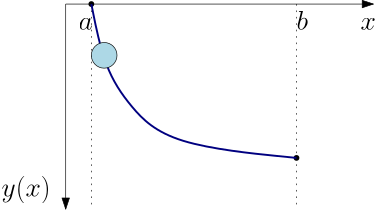

Another classical problem mentioned in every textbook on calculus of variations is the problem of brachistochrone, where the task is to find a shape of a thin wire with a bead sliding along it (with no friction) in the shortest time, see Fig. 4.

You may also like watching the “no-equation” video by VSauce:

The cost function is simply the total time, that is J = \int_{t_\mathrm{i}}^{t_\mathrm{f}} \mathrm{d}t = t_\mathrm{f}-t_\mathrm{i}.

It does not fit into the framework that we currently use because time enters here as the independent variable. But there is an easy fix to this. We will express time as a ratio of the distance and velocity. In particular, J = \int_a^b \frac{\text{d}s}{v}.

We are already well familiar with the numerator but the velocity in the denominator needs to be determined too. We will use a physical argument here: when the bead is in the initial position, the velocity is zero and the height (as measured along the y axis) is zero. Therefore the total energy given as a sum of kinetic and potential energies \mathcal{T}+\mathcal{V} is zero. And since we assume no friction, the total energy remains constant along the whole trajectory, that is, \frac{1}{2}mv^2 - mgy = 0, from which we can write v(x) = \sqrt{2gy(x)}.

We can then write the expression for the total time as J = \int_a^b \frac{\text{d}s}{v}= \int_a^b \frac{\sqrt{1+(y'(x))^2}}{\sqrt{2gy(x)}}\text{d}x.

The optimization problem is then \operatorname*{minimize}_{y\in\mathcal{C}^1_{[a,b]}} \int_a^b \sqrt{\frac{1+(y'(x))^2}{2gy(x)}}\text{d}x.

Basic problem of calculus of variations with fixed ends

The only motivation for including those few simple examples was to justify the following general problem. We will call this . We will keep considering \mathcal{C}^1 functions of x defined on an interval [a,b] with the values at the beginning and end of the interval fixed

y(a) = \mathrm y_a,\qquad y(a) = \mathrm y_b,

see Fig. 5 and the task is to find y^\star\in\mathcal{C}^1_{[a,b]} minimizing the functional of the following type

J(y(\cdot)) = \int_a^b L(x,y(x),y'(x))\text{d}x.

The basic problem of calculus of variations is then \boxed{ \begin{aligned} \operatorname*{minimize}_{y\in\mathcal{C}^1_{[a,b]}} &\quad \int_a^b L(x,y(x),y'(x))\text{d}x\\ \text{subject to} &\quad y(a) = \mathrm y_a,\\ &\quad y(b) = \mathrm y_b. \end{aligned}}

It is possible to extend this basic problem formulation into something more complicated, for example by relaxing the ends and add constraints, but will only have a look at those extensions later. First, we solve the basic problem and see if we can use it within the optimal control framework.

In order to state the first-order necessary condition of optimality, we need to find the variation of the cost functional. But we already know that we can form it from the partial derivative of the cost functional with respect to some real parameter as in Eq. 6, that is,

\begin{aligned} \frac{\mathrm{d} J(y^\star(x)+\alpha\eta(x))}{\mathrm{d} \alpha} &= \frac{\mathrm d}{\mathrm d \alpha}\int_a^b[L(x,y^\star+\alpha\eta,(y^\star)'+\alpha\eta')]\text{d}x,\nonumber\\ &= \int_a^b \frac{\mathrm d}{\mathrm d \alpha}[L(x,y^\star+\alpha\eta,(y^\star)'+\alpha\eta')]\text{d}x,\nonumber\\ &= \int_a^b \left[ \frac{\partial L(x,y,y')}{\partial y}\eta(x) + \frac{\partial L(x,y,y')}{\partial y'}\eta'(x)\right]\text{d}x \end{aligned}

Now, setting this equal to zero, we do not learn much because the arbitrary \eta(\cdot) and also its derivative appear in the conditions. It will be much better if we can modify this into something like \int_a^b \left[ (\qquad )\eta(x)\right]\text{d}x. Why should we aim at this form? The fundamental lemma of calculus of variations says that if the following holds for any \eta\in\mathcal{C}^1_{[a,b]} vanishing at a and b \int_a^b \xi(x)\eta(x)\text{d}x = 0, then necessarily \xi(x)\equiv 0 identically on the whole interval [a,b]. The proof can be found elsewhere.

Hence we are motivated to bring the formula for the variation into the format where the derivative of \eta is missing. This will be accomplished by applying the per-partes integration to the term \int_a^b\frac{\partial L(x,y,y')}{\partial y'}\eta'(x)\text{d}x: \int_a^b\frac{\partial L(x,y,y')}{\partial y'}\eta'(x)\text{d}x = \left[\frac{\partial L(x,y,y')}{\partial y'}\eta(x)\right]_{a}^b-\int_a^b\frac{\text{d}}{\text{d}x}\frac{\partial L(x,y,y')}{\partial y'}\eta(x)\text{d}x.

Substituting back to our expression for the variation, we get \frac{\mathrm{d} J}{\mathrm{d} \alpha} = \left[\frac{\partial L(x,y,y')}{\partial y'}\eta(x)\right]_{a}^b + \int_a^b \left( \frac{\partial L(x,y,y')}{\partial y}-\frac{\text{d}}{\text{d}x}\frac{\partial L(x,y,y')}{\partial y'}\right)\eta(x)\text{d}x. \tag{7}

The first term on the right is zero because we assumed at the very beginning that the function y(\cdot) is fixed at both ends, hence the variation \delta y(\cdot) is zero at both ends, hence \eta(a)=\eta(b)=0. As a result, we have the following equation \boxed{ \frac{\partial L(x,y,y')}{\partial y}-\frac{\text{d}}{\text{d}x}\frac{\partial L(x,y,y')}{\partial y'} = 0} \tag{8} or \boxed{ \frac{\partial L(x,y,y')}{\partial y}=\frac{\text{d}}{\text{d}x}\frac{\partial L(x,y,y')}{\partial y'}.} \tag{9}

This is the famous Euler-Lagrange equation.

My biased opinion is that Euler-Lagrage equation is a result that deserves its position in the list of top ten quations in applied mathematics.

Smooth function which satisfy the Euler-Lagrange equation are called extremals. They play the same role within calculus of variations as stationary points do within differential calculus, that is, they are just candidate functions for a minimizer. This is another way of saying that the Euler-Lagrange equation provides necessary conditions of optimality.

Finally, we format this result within the variational framework. We can now invoke Eq. 10 and write it as \delta J = \int_a^b \underbrace{\left[\frac{\partial L(x,y,y')}{\partial y}-\frac{\text{d}}{\text{d}x}\frac{\partial L(x,y,y')}{\partial y'}\right]}_{\frac{\delta J}{\delta y(x)}} \, \underbrace{\delta y(x)}_{\alpha \eta(x)}\mathrm d x, \tag{10} from which we can see that the left hand side of the Euler-Lagrange equation gives us the variational derivative that we were looking for.

You may now wonder why on earth did we actually bother to introduce the new concept of a variation (of a function and of a functional)? We were able to derive the Euler-Lagrange equation just using a partial derivative with respect to \alpha. Good point. In fact, the major motivation was to develop a framework that would resemble that of differential calculus as closely as possible. Knowing now the resulting format of the first-order necessary conditions of optimality, let’s now try to rederive it in the fully variational style. That is, we want to find the variation \delta J of the functional J(y(x)) that is given by the integral \delta J = \delta\int_a^b L(x,y,y')\mathrm d x.

The variation now constitutes an operation pretty much mimicking the differential when it comes to dealing with composite functions, products of two function and other situations. Namely, for constant lower and upper bounds in the integral we can move the variation operation into the integral \delta J = \int_a^b \delta L(x,y,y')\mathrm d x and then, following the standard rules (shared with operation of differentiation), we get \delta J = \int_a^b \left[ \frac{\partial L(x,y,y')}{\partial x}\delta x + \frac{\partial L(x,y,y')}{\partial y}\delta y + \frac{\partial L(x,y,y')}{\partial y'}\delta y'\right]\mathrm d x.

Now, x is an independent variable, hence it does not vary and \delta x = 0. Furthermore, the operations of variation and derivative with respect to x commute, therefore \delta y', which is a shorthand notation for \delta\left(\frac{\mathrm d}{\mathrm d x} y(x)\right) can be rewritten as \delta y'(x)= \frac{\mathrm d}{\mathrm d x} (\delta y(x)) and we can write the variation of the cost function as \delta J = \int_a^b \left[\frac{\partial L(x,y,y')}{\partial y}\delta y + \frac{\partial L(x,y,y')}{\partial y'} (\delta y(x))' \right]\mathrm d x.

Identically as in our previous development, we can get rid of the derivative of the variation using integration , which gives \boxed{ \delta J = \left[\frac{\partial L(x,y,y')}{\partial y'}\delta y(x)\right]_{a}^b + \int_a^b \left( \frac{\partial L(x,y,y')}{\partial y}-\frac{\text{d}}{\text{d}x}\frac{\partial L(x,y,y')}{\partial y'}\right)\delta y(x)\text{d}x,} \tag{11} which under the assumption of fixed both ends, that is, \delta y(a) = \delta y(b) = 0, gives the Euler-Lagrange equation. Elegant procedure, isn’t it?

This can perhaps be regarded as culmination of our attempts to develop calculus of variations as an analogy to differential calculus.

To make the notation a bit more compact, we will often write the partial derivative of L(x,y,y') with respect to y(x) as L_y. Similarly, the partial of the same function with respect to y'(x) as L_{y'}. Using this notation, we can immediately show that Euler-Lagrange equation is actually a second-order ordinary differential equation \boxed{ L_y - L_{y'x} - L_{y'y}y' - L_{y'y'}y'' = 0.} \tag{12}

In order to see how we got this, first recall that L is a function of x, y(x) and y'(x). Let’s write it explicitly as L(x,y(x),y'(x)). Then, in the Euler-Lagrange equation we need to find the total derivative of L_{y'} with respect to x, that is, we need \frac{\mathrm d}{\mathrm dx}L_{y'}, and we invoke the chain rule for this. Remember, the function L_{y'} is generally (!) a function of three arguments too: x, y and y'. Therefore, applying the chain rule we will get three terms:

\frac{\mathrm d}{\mathrm dx}L_{y'}(x,y,y') = \underbrace{\frac{\partial L_{y'}}{\partial x}}_{L_{y'x}} + \underbrace{\frac{\partial L_{y'}}{\partial y}}_{L_{y'y}} \underbrace{\frac{\mathrm d y(x)}{\mathrm d x}}_{y'} + \underbrace{\frac{\partial L_{y'}}{\partial y'}}_{L_{y'y'}} \underbrace{\frac{\mathrm d y'(x)}{\mathrm d x}}_{y''}.

That is it. Combine it with the other term L_y from the E.-L. equation and we are done.

We know that in order to specify a solution of a second-order ODE completely, we need to provide two values. Sometimes we specify them at the beginning of the interval, in which case we would give the value of the function and its derivative. This is the well-known initial value problem (IVP). On some other occasions, we specify the values at two different points on the interval. And this is our case here. In particular, here we have y(a)=\mathrm y_a and y(b)=\mathrm y_b, which turns the problem into so-called boundary value problem (BVP). Both analysis and (numerical) methods for finding a solution of boundary value problems are a way more difficult that for initial value problems. But there are dedicated solvers (see the section on software).

Nonetheless, before jumping into calling some numerical solvers, let’s get some insight for two special cases by analyzing the situations carefully. First, assume that L does not depend on y. We call this a “no y case”. Then the Euler-Lagrange equation simplifies to 0 = \frac{\text{d}}{\text{d}x}L_{y'}, and, as a consequence, L_{y'} is constant, independent of x.

The second special case is the “no x case”. Then L_y - L_{y'y}y' - L_{y'y'}y'' = 0.

By multiplying both sides by y' (and some one-line work), the equation turns into \frac{\text{d}}{\text{d}x}( L_{y'}y' - L ) = 0.

As a consequence, L_{y'}y' - L is constant along the optimal curve.

The two new functions whose values are preserved along the extremal (under the respective conditions) are so special that they deserve their own symbols and names: \boxed{ p(x) \coloneqq L_{y'},} and the choice of the symbol p is intentional as this variable plays the role of momentum in physics (when the independent variable x is time and L is the difference between the kinetic and potential energies), and \boxed{ H(x,y,y',p) \coloneqq py'-L} and the choice of the symbol H is intentional becase this variable plays the role of Hamiltonian in physics.

Let us now see how y and p develop as functions of x, and we will use Hamiltonian for that purpose. First, it is immediate from the definition of Hamiltonian that y' = H_p.

Similarly, the derivative of momentum is p' = \frac{\text{d}}{\text{d}x} L_{y'} = L_y = -H_y, where the second equality comes from Euler-Lagrange equation and the third one comes from the definition of H. We format the two differential equations as one vector differential equation \boxed{ \begin{bmatrix} y' \\ p' \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} H_p \\ -H_y \end{bmatrix}}

This version of first-order necessary conditions is no less famous in physics and theoretical mechanics – Hamilton’s canonical equations – and some of our results on optimal control will come in this format.

Example 2 Let us now see how the analysis of the special cases can be practically useful. We will only have a look at the minimum distance problem. The Lagrangian is L(y') = \sqrt{1+(y')^2}, which is clearly independent of y (and of x as well). Therefore L_{y'} = \frac{1}{2}\frac{2y'}{\sqrt{1+(y')^2}} must be constant. The only way is to have y'(x) constant, that is, the graph of the function y(x) must be a line. Introducing the boundary conditions, it is now obvious that the solution is a line connecting the two points.

One important general property will be revealed if we differentiate H with respect to y' H_{y'}(x,y,y',p) = p-L_{y'}.

If p is chosen as L_{y'}, the derivative of Hamiltonian vanishes. In other words, when H is evaluated on the curve, it has a stationary point with respect to the third variable. To support this mental step of regarding the third (input) argument as independent from the rest, we write the Hamiltonian for the extremal with the third variable relaxed as H(x,y,z,p). The above result says that \boxed{ \left.\frac{\partial H(x,y,z,p)}{\partial z}\right|_{z = y', \, p = L_{y'}} = 0}.

In fact, as we will see shortly, Hamiltonian is not only stationary along the optimal trajectory but it also achieves the maximum value! This will actually turn out the crucial property of a Hamiltonian – it is maximized along the optimal trajectory with respect to y'. The fact that the derivative is zero is just a consequence in the special case when such derivative exists.

Sufficient conditions of optimality (minimum)

What remains to be done before we come to applying the Euler-Lagrange equation to control problems is to discuss how we can learn if the extremal is actually minimizing the cost functional. Or maximizing it? Or what if it is just a saddle “point”? The mathematics needed to answer these questions is quite delicate, we will only sketch the direction of reasoning and for complete proofs refer to the literature.

Knowing that the first variation vanishes for an extremal, higher order terms need to be investigated, starting with the term in the Taylor’s expansion corresponding to the squared variations. Similarly as in the finite-dimensional optimization, we first argue that for small enough \alpha, the second-order term dominates all the higher order terms and then we study under which conditions is the second order term nonnegative (for the second-order necessary condition) or positive (for the second-order sufficient condition).

The answer for the necessity part, which relies heavily on the fact that we have decided to work with the \|.\|_1 norm, is that L_{y'y'} \geq 0 needs to be satisfied. This is called the Legendre necessary condition. We have certainly skipped a lot of nontrivial work that needs to be done to show this result. Check the literature for details if you are interested.

The sufficiency part is even more complicated. It turns out that merely sharpening the necessary Legendre condition into L_{y'y'} > 0 is not enough to guarantee the minimality. The additional constraint is quite convoluted even to be stated. It is called Jacobi condition and has something to do with absence of conjugate points on the interval of control. The only motivation for stating these terms here without actually providing any explanation is just to provide the keywords and search phrases for learning more elsewhere. Here we just state that the optimality is guaranteed if the inverval of x is not “too long”… This is certainly too vague, but the reason why we are so easy-going here is that once we switch to optimal control, we will have other – and more convenient – tools to guarantee the optimality.

We now move on to one crucial observation: H_{y'y'} = -L_{y'y'}.

Hence, if a given function y minimizes J, then L_{y'y'}\geq 0 and H_{y'y'} \leq 0, \tag{13} which reads that Hamiltonian achieves a maximum when evaluated on the optimal curve. It can be restated as \boxed{ H(t,y,y',p) \geq H(t,y,z,p)} for all z\in\mathcal{C}^1 on the interval [a,b] and close to y'(t) (in the sense of 1-norm).

This is a key property and constitutes a prequel to the celebrated Pontryagin’s principle of maximum that we are going to study in the next chapter.

Constrained problems in calculus of variations

Now that we have covered the first-order and second-order necessary conditions of optimality and at least touched the second-order sufficient conditions of optimality, we should start discussing constraints. Here we will only investigate equality type-constraints. The inequality-type constraints are beyond the reach of basic methods of calculus of variations. But as we will see, an offspring of calculus of variations – the already mentioned Pontryagin’s principle – will handle these easily, at least in some cases.

The constraints that we are going to encounter in optimal control come in the form of differential equations, and these constitute pointwise constraints F(x,y,y')=0.

For every value of the independent variable x, we have one constraint. Since x is real, we have a continuum of constraints. As a consequence, we will need an infinite number of Lagrange multipliers as well— in other words, the Lagrange multiplier will be a function of x too. The augmented cost function is J^\text{aug}(y(\cdot)) = \int_a^b L(x,y,y')\text{d}x + \int_a^b \lambda(x)\cdot F(x,y,y')\text{d}x, where the symbol "\cdot`` is there to emphasize that in the case when both y and \lambda are vector functions (hence F is a vector), the second integrand is obtained as an inner product. Rewriting the above expression for the augmented criterion of optimality as J^\text{aug}(y) = \int_a^b \left [L(x,y,y')+\lambda(x)\cdot F(x,y,y')\right ]\text{d}x suggests that we can introduce an augmented Lagrangian L^\text{aug}(x,y,y',\lambda) = L(x,y,y')+\lambda(x)\cdot F(x,y,y') and continue as we did in the unconstrained case. For completeness, let’s state here that in the case of vector functions, the augmented Lagrangian is given as L^\text{aug}(x,y,y',\lambda) = L(x,y,y')+\lambda(x)^{\top} F(x,y,y'), or, using the alternative notation for the inner product, L^\text{aug}(x,y,y',\lambda) = L(x,y,y')+\langle \lambda(x), F(x,y,y')\rangle,

A word of warning is needed here, though. Similarly as in the unconstrained case, it can happen that the constraints will be degenerate, in which case the Euler-Lagrange equation fails to be a necessary condition of optimality. We will not discuss this delicate issue here and rather direct the interested student to the literature.

This is roughly it. This is what we need from calculus of variations to get started with optimal control in continuous-time setting.