a = 1/2

b = 1

q = 2

r = 3

p₂ = b^2

p₁ = (r - r*a^2 - b^2*q)

p₀ = -r*q

s₁, s₂ = (-p₁ + sqrt(p₁^2 - 4*p₂*p₀))/(2*p₂), (-p₁ - sqrt(p₁^2 - 4*p₂*p₀))/(2*p₂)(2.327677108793573, -2.577677108793573)In this section we are going to solve the LQR problem on the time horizon extended to infinity, that is, our goal is to find an infinite (vector) control sequence \bm u_0, \bm u_{1},\ldots, \bm u_{\infty} that minimizes J_0^\infty = \frac{1}{2}\sum_{k=0}^{\infty}\left[\bm x_k^\top \mathbf Q \bm x_k+\bm u_k^\top \mathbf R\bm u_k\right], where, as before \mathbf Q = \mathbf Q^\top \succeq 0 and \mathbf R = \mathbf R^\top \succ 0, and the system is modelled by \bm x_{k+1} = \mathbf A \bm x_{k} + \mathbf B \bm u_k, \qquad \bm x_0 = \mathbf x_0.

There is no penalty on the terminal state in the infinite time horizon LQR problem.

The first question that inevitably pops up is the one about the motivation for introducing the infinite time horizon: does the introduction of an infinite time horizon meant that we do not care about when the controller accomplishes the task? No, certainly it does not.

The infinite time horizon can be used in scenarios when the final time is not given and we leave it up to the controller to take as much time as it needs to reach the desired state. But even then we can still express our preference for reaching the target state quickly by increasing the weights in \mathbf Q against \mathbf R.

The infinite time horizon can also be used to model the case when the system is expected to operate indefinitely. This is a common scenario in practice, for example, in the case of temperature control in a building – there is no explicit end of the control task.

We have seen in the previous section that the solution to the LQR problem with a free final state and a finite time horizon is given by a time-varying state feedback control law \bm u_k = \mathbf K_k \bm x_k. The sequence of gains \mathbf K_k for k=0,\ldots, N-1, is given by the sequence of matrices \mathbf S_k for k=0,\ldots, N, which in turn is given as the solution to the (discrete-time) Riccati equation initialized by the matric \mathbf S_N specifying the terminal cost, and solved backwards in time. But we have also seen, using an example, that if the time interval was long enough, the sequences \mathbf K_k and \mathbf S_k both converged to some steady state values as the time k proceeded backwards towards the beginning of the time interval.

While using these steady-state values instead of the full sequences leads to a suboptimal solution on a finite time horizon, it turns out that it actually gives the optimal solution on an infinite time horizon. Although our argument here is as rather hand-wavy, it is intuitive — there is no end to the time interval, hence the steady-state values are not given a chance to change “towards the end”, as we observed in the finite time horizon case.

Other approaches exist for solving the infinite time horizon LQR problem that do not make any reference to the finite time horizon problem. Some of them are very elegant and concise, but here we intentionally stick to viewing the infinite horizon problem as a natural extension of the finite horizon problem.

Before we proceed with the discussion of how to find the steady-state values (the limits) of \mathbf S_k and subsequently \mathbf K_k, we must discuss the notation. While increasing the time horizon N, the solution to the Riccati equation settles towards the beginning of the time interval. We can thenk pick the steady-state values right at the initial time k=0, that is, \mathbf S_0 and \mathbf K_0. But thanks to time invariance, we can also fix the final time to some (arbitrary) N and strech the interval by moving its beginning toward -\infty. The limits of the sequences \mathbf S_k and \mathbf K_k can be considered as k \rightarrow -\infty. It seems appropriate to denote these limits as \mathbf S_{-\infty} and \mathbf K_{-\infty} then. However, the notation used for these limits in the literature is just \mathbf S_\infty and \mathbf K_\infty \mathbf S_\infty \coloneqq \lim_{k\rightarrow -\infty} \mathbf S_k, \qquad \mathbf K_\infty \coloneqq \lim_{k\rightarrow -\infty} \mathbf K_k.

Leaving aside for the moment the important question whether and under which conditions such a limit \mathbf S_\infty exists, the immediate question is how to compute such limit. One straightforward strategy is to run the recurrent scheme (Riccati equation) and generate the sequence \mathbf S_{N}, \mathbf S_{N-1}, \mathbf S_{N-2}, \ldots so long as there is a nonnegligible improvement, that is, once \mathbf S_{k}\approx\mathbf S_{k+1}, stop iterating. That is certainly doable.

There is, however, another idea. We apply the steady-state condition \mathbf S_{\infty} = \mathbf S_k=\mathbf S_{k+1} to the Riccati equation. The resulting equation \boxed{ \mathbf S_{\infty}=\mathbf A^\top\left[\mathbf S_{\infty}-\mathbf S_{\infty}\mathbf B(\mathbf B^\top\mathbf S_{\infty}\mathbf B+\mathbf R)^{-1}\mathbf B^\top\mathbf S_{\infty}\right]\mathbf A+\mathbf Q} is called discrete-time algebraic Riccati equation (DARE) and it is one of the most important equations in the field of computational control design.

The equation may look quite “messy” and does not necessarily offer any insight. But recall the good advice to shrink the problem to the scalar size while studying matrix-vector expressions and struggling to get some insight. Our DARE simplifies to s_\infty = a^2s_\infty - \frac{a^2b^2s_\infty^2}{b^2s_\infty+r} + q

Multiplying both sides by the denominator we get the equivalent quadratic (in s_\infty) equation \boxed{ b^2s_\infty^2 + (r - ra^2 - qb^2)s_\infty - qr = 0.} \tag{1}

Voilà! A scalar DARE is just a quadratic equation, for which the solutions can be found readily.

There is a caveat here, though, reflected in using plural in “solutions” above. Quadratic equation can have two (or none) real solutions!

Example 1 (Two solutions to the scalar DARE)

a = 1/2

b = 1

q = 2

r = 3

p₂ = b^2

p₁ = (r - r*a^2 - b^2*q)

p₀ = -r*q

s₁, s₂ = (-p₁ + sqrt(p₁^2 - 4*p₂*p₀))/(2*p₂), (-p₁ - sqrt(p₁^2 - 4*p₂*p₀))/(2*p₂)(2.327677108793573, -2.577677108793573)But the sequence produced by original discrete-time recurrent Riccati equation is determined uniquely by s_N! What’s up? How are the solutions to ARE related to the limiting solution of recursive Riccati equation? Answering this question will keep us busy for the rest of this lecture. We will structure this broad question into several sub-questions

Let us state the answer first: the system \bm x_{k+1}=\mathbf A \bm x_k+\mathbf B \bm u_k must be stabilizable in order to guarantee existence of a bounded limiting solution \mathbf S_\infty to Riccati solution.

To see this, note that for a stabilizable system, we can find some time-invariant feedback gain, which guarantes that \bm x_k\rightarrow 0 as k\rightarrow \infty. Note, once again, that for LTI systems the situation with fixed and finite N and k going toward -\infty, can be viewed equivalently as if k goes from 0 to \infty. Invoking this and recalling also that our cost is J_i = \frac{1}{2}\bm x_N^\top\mathbf S_N \bm x_N + \frac{1}{2}\sum_{k=i}^{N-1}\bm x_k^\top\mathbf Q \bm x_k + \bm u_k^\top\mathbf R \bm u_k, we can argue that \lim_{i\rightarrow -\infty} J_i is finite. At the same moment, the cost function J_i at any i for any suboptimal feedback gain must be higher or equal to the cost function for the optimal state feedback gain; this is the very definition of an optimal solution: J_i \geq J_i^\star.

Therefore \mathbf x_i^\top\mathbf S_i \mathbf x_i \geq \mathbf x_i^\top\mathbf S_i^\star \mathbf x_i, which can also be written as \mathbf S_i \succeq \mathbf S_i^\star.

In other words, we have just shown that for a stabilizable system the optimal sequence \mathbf S_k is bounded at every k.

Two more properties of the optimal \mathbf S_k can be identified upon consulting the Riccati equation:

\mathbf S_k is symmetric. This is obvious once we observe that by transposing the Riccati equation \mathbf S_k = \mathbf Q + \mathbf A^\top\mathbf S_{k+1}\mathbf A - \mathbf A^\top\mathbf S_{k+1}\mathbf B( \mathbf B^\top\mathbf S_{k+1}\mathbf B+\mathbf R)^{-1}\mathbf B^\top\mathbf S_{k+1}\mathbf A, we obtain the same expression.

\mathbf S_k\succeq \mathbf 0 if \mathbf S_N\succeq \mathbf 0. This is perhaps best shown with the form of Riccati equation

\mathbf S_k = \mathbf Q+\mathbf A^\top\mathbf S_{k+1}(\mathbf I+\mathbf B\mathbf R^{-1}\mathbf B^\top\mathbf S_{k+1})^{-1}\mathbf A,

just use the rules such as that a squared matrix is always positive semidefinite, and that a sum of two semidefinite matrices is a semidefinite matrix. As usual, resorting to scalars will lend some insight.

Now, let’s skip the second of our three original questions (the one about uniqueness) temporarily and focus on the third question. In order to answer it, let us extend our state-space model with the artificial output equation \bm y_k = \begin{bmatrix} \mathbf C \\ \mathbf 0 \end{bmatrix} \bm x_k + \begin{bmatrix} \mathbf 0 \\ \mathbf D \end{bmatrix} \bm u_k,\quad k=0,1,\ldots, N-1,\qquad \bm y_N = \begin{bmatrix} \mathbf C \\ \mathbf 0 \end{bmatrix} \bm x_N, where \mathbf Q=\mathbf C^\top\mathbf C, \mathbf R=\mathbf D^\top\mathbf D and \mathbf S_N=\mathbf C_N^\top\mathbf C_N. With this new artificial system, our original optimization criterion can be rewritten J_i = \frac{1}{2}\bm y_N^\top\bm y_N + \frac{1}{2}\sum_{k=i}^{N-1} \bm y_k^\top\bm y_k = \frac{1}{2}\sum_{k=i}^{N} \bm y_k^\top\bm y_k.

From the previous analysis we know that thanks to stabilizability, the optimal cost function is always bounded (by a finite cost for any suboptimal stabilizing controller) J_{\infty}^\star = \frac{1}{2}\sum_{k=i}^\infty\bm y_k^\top\bm y_k< \infty.

Having a bounded sum of an infinite number of squared terms, it follows that \|\bm y_k\|\rightarrow 0 as k\rightarrow \infty, and therefore \bm y_k\rightarrow 0 as k\rightarrow \infty. The crucial question now is: does the fact that \mathbf C \bm x_k\rightarrow 0 and \mathbf D \bm u_k\rightarrow 0 for k\rightarrow \infty also imply that \bm x_k \rightarrow 0 and \bm u_k \rightarrow 0?

Since |\mathbf R|\neq 0, \bm u_k\rightarrow 0. But we made no such restrictive assumption about \mathbf Q. In the very extreme case assume that \mathbf Q=\mathbf 0. What will happen with an unstable system is that our optimization criterion only contains the control sequence \bm u_k and it naturally minimizes the total cost by setting \bm u_k = \bm 0. The result is catastrophic — the system goes unstable. The fact that the state variables \bm x_k of the system blow up goes unnoticed by the optimization cost function. The easiest fix of this situation is to require \mathbf Q nonsigular as we did for \mathbf R (for other reasons), but this maybe too restrictive. We will shortly see an example where nonsingular weighting matrix \mathbf Q might be useful.

The ultimate condition under which the blowing up of the system state variables is always reflected in the optimization cost is the detectability of the artificial system given by the matrix pair (\mathbf A,\mathbf C). In practice, we may check for observability (similarly as we do for controllability instead of detectability) but doing so we request more then is needed.

The last issue that we have to solve is uniqueness. Why do we need to care? We have already discussed that the ARE, being a quadratic equation, can have more than just one solution. In the scalar case it can have two real solutions (or no real because both complex). In general there are then several posibilities

Our goal is to study if we can exclude the last scenario – multiple positive semidefinite solutions of ARE. Provided the system is stabilizable, we know that one of them is our optimal solution but we will have troubles to identify the correct solution. In other words, we are asking if there is a unique stabilizing solution to ARE. We will use ARE in the Joseph stabilized form \mathbf S = (\mathbf A-\mathbf B\mathbf K)^\top \mathbf S(\mathbf A-\mathbf B\mathbf K) + \mathbf K^\top \mathbf R\mathbf K + \mathbf Q, in which we stop using \infty in the lower index for notational brevity. Using our factorization of \mathbf Q and \mathbf R we can write the Riccati equation as \mathbf S = (\mathbf A-\mathbf B\mathbf K)^\top \mathbf S(\mathbf A-\mathbf B\mathbf K) + \begin{bmatrix}\mathbf C^\top& \mathbf K\mathbf D^\top\end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix}\mathbf C\\ \mathbf D\mathbf K\end{bmatrix}.

Observe that for a fixed (optimal) \mathbf K the above equation is actually a Lyapunov equation for an equivalent system with the state matrices (\mathbf A-\mathbf B\mathbf K,\begin{bmatrix}\mathbf C\\ \mathbf D\mathbf K\end{bmatrix}). We have already refreshed the well-known facts about Lypunov equation that provided the system is stable (and in our case it is since (\mathbf A-\mathbf B\mathbf K) matrix is) and observable, the equation has a unique positive definite solution. If observability is not guranteeed, there is a positive definite solution.

Clearly, what remains to be shown is that the system (\mathbf A-\mathbf B\mathbf K,\begin{bmatrix}\mathbf C\\ \mathbf D\mathbf K\end{bmatrix}) is observable. Let us invoke one of the tests of observability — the popular PBH test. For a system (\mathbf A, \mathbf C) it consists in creating a matrix \begin{bmatrix}z\mathbf I - \mathbf A\\ \mathbf C\end{bmatrix} and checking if it is full rank for every complex z. In our case this test specializes to checking the rank of \begin{bmatrix}z\mathbf I - (\mathbf A-\mathbf B\mathbf K)\\ \mathbf C\\ \mathbf D\mathbf K\end{bmatrix}, which can be shown to be equal to the rank of \begin{bmatrix}z\mathbf I - \mathbf A\\ \mathbf C\\ \mathbf D\mathbf K\end{bmatrix}.

This expresses the well-known fact from linear systems that state feedback preserves observability. If \mathbf K can be arbitrary, the only way to keep this rank full is to guarantee that \begin{bmatrix}z\mathbf I - \mathbf A\\ \mathbf C\end{bmatrix} is full rank. In other words, the system (\mathbf A, \mathbf C), where \mathbf C=\sqrt{\mathbf Q}, must be observable.

Let us summarize the findings: although detectability of (\mathbf A, \mathbf C) is enough to guarantee the existence of a positive semidefinite \mathbf S which stabilizes the system, if the detectability condition is made stronger by requiring observability, it is guaranteed that there will be a unique positive definite solution to ARE.

Why do we need to care about positive definiteness of \mathbf S? Let us consider a scalar case for illustration again, in particular the scalar DARE in Eq. 1. Trivial analysis shows that for q=0, one of the roots is s_1=0 and the other is always s_2<0. Hence the solution of ARE that represents the steady-state solution of the recurrent Riccati equation is s=0.

Example 2 (Unique positive semidefinite solution to the scalar DARE)

a = 1/2

b = 1

q = 0

r = 3

p₂ = b^2

p₁ = (r - r*a^2 - b^2*q)

p₀ = -r*q

s₁, s₂ = (-p₁ + sqrt(p₁^2 - 4*p₂*p₀))/(2*p₂), (-p₁ - sqrt(p₁^2 - 4*p₂*p₀))/(2*p₂)(0.0, -2.25)As a consequence, the optimal state-feedback gain is k=0. For an unstable system this would be unacceptable but for a stable system this makes sense: the system is stable even withouth the control, therefore, when the state is not penalized in the criterion at all (q=0), the optimal strategy is not to regulate at all. Mathematically correct. Nonethelesss, from an engineering viewpoint we may be quite unhappy because the role of the feedback regulator is also to attenuate the influence of external disturbances. Our optimal state-feedback regulator does not help at all in these situation. That is why we may want to require positive definite solution of ARE (by strengtheing the condition from detectability to observability of (\mathbf A,\sqrt{\mathbf Q})).

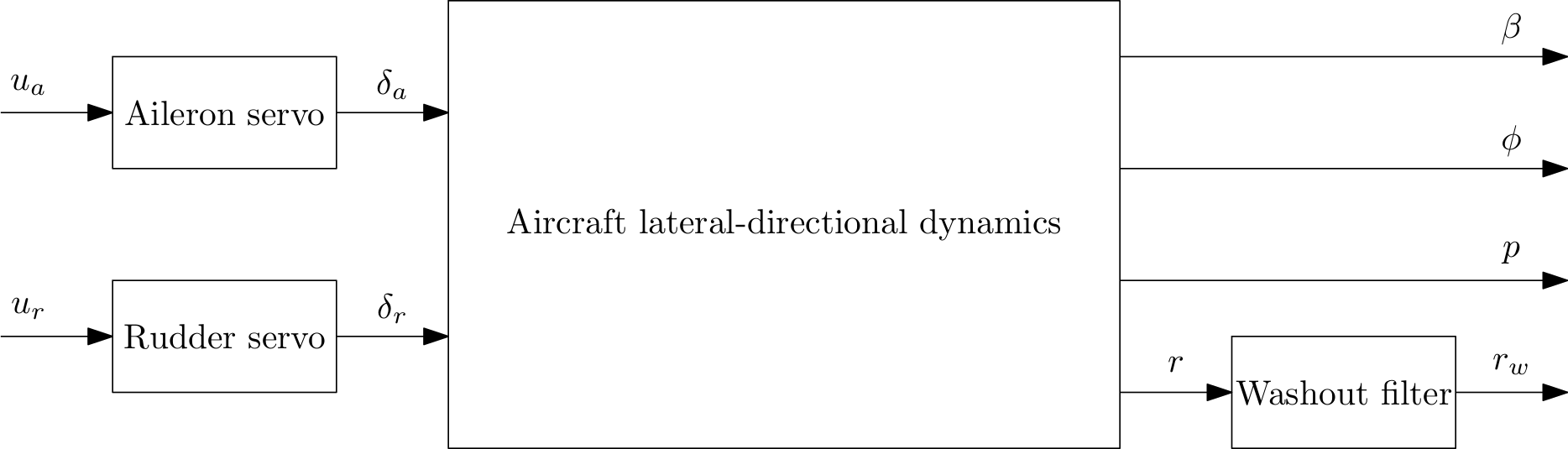

Example 3 (LQR design for lateral-directional dynamics of the F16 aircraft) This is Example 5.3-1 from [1, p. 407]. A linear model of lateral-directional dynamics of F16 trimmed at: VT=502ft/s, 302psf dynamic pressure, cg @ 0.35cbar. It also includes the dynamics of ailerons and rudders and washout filter. The system has two inputs (the commands to the control surfaces), four state variables corresponding to the lateral-directional dynamics of the aircraft, two state variables corresponding to the servo dynamics, and one more corresponding to the washout filter. We assume that all the state variables are available for state feedback (they are measured or estimated).

| Symbol | Name | Units |

|---|---|---|

| u_\mathrm{a} | reference for the aileron deflection | rad |

| u_\mathrm{r} | reference for the rudder deflection | rad |

| \delta_\mathrm{a} | true aileron deflection | rad |

| \delta_\mathrm{r} | true rudder deflection | rad |

| \beta | sideslip angle | rad |

| \phi | bank angle | rad |

| p | roll rate | rad/s |

| r | yaw rate | rad/s |

| r_\mathrm{w} | measured yaw rate (after washout) | rad/s |

The code that defines the discrete-time state-space model follows

A = [-0.3220 0.0640 0.0364 -0.9917 0.0003 0.0008 0;

0 0 1 0.0037 0 0 0;

-30.6492 0 -3.6784 0.6646 -0.7333 0.1315 0;

8.5396 0 -0.0254 -0.4764 -0.0319 -0.062 0;

0 0 0 0 -20.2 0 0;

0 0 0 0 0 -20.2 0;

0 0 0 57.2958 0 0 -1]

B = [0 0;

0 0;

0 0;

0 0;

20.2 0;

0 20.2;

0 0]

C = [0 0 0 57.2958 0 0 -1;

0 0 57.2958 0 0 0 0;

57.2958 0 0 0 0 0 0;

0 57.2958 0 0 0 0 0]

# The `C` matrix is only defined for plotting purposes as it converts from radians to degrees.

using ControlSystems, LinearAlgebra

G = ss(A,B,C,0)

# Conversion of the model to discrete time

Ts = 0.1 # sampling period

Gd = c2d(G,Ts) # discretized system

A,B,C,D = Gd.A,Gd.B,Gd.C,Gd.D([0.9226667967276305 0.0061993687563318516 … 0.0002121726335909019 0.0; -0.1324663143618211 0.9997066454002713 … 0.00031188493568957813 0.0; … ; 0.0 0.0 … 0.13265546508012172 0.0; 2.292290658677099 0.004976965360488232 … -0.009375212477843127 0.9048374180359594], [2.821613795894789e-5 0.00018468401795193416; -0.001449606139792144 0.00025320960350156183; … ; 0.0 0.8673445349198778; -0.0037522412534400328 -0.007373986216857326], [0.0 0.0 … 0.0 -1.0; 0.0 0.0 … 0.0 0.0; 57.2958 0.0 … 0.0 0.0; 0.0 57.2958 … 0.0 0.0], [0.0 0.0; 0.0 0.0; 0.0 0.0; 0.0 0.0])And in the following code we define the weights for the LQR controller and design the controller

q_beta = 100.0

q_phi = 100

q_p = 1

q_r = 1

q_rw = 1

q = [q_beta, q_phi, q_p, q_r, 0, 0, q_rw]

Q = diagm(0=>q)

r_a = 10.0

r_r = 10.0

r = [r_a, r_r]

R = diagm(0=>r)2×2 Matrix{Float64}:

10.0 0.0

0.0 10.0Note how we do not penalize the fifth and sixth state variables, \delta_\mathrm{a} and \delta_\mathrm{r}, respectively, because these are just low-pass filtered control inputs, and the control inputs are already penalized with the \mathbf R matrix. But we must check if the stabilizability and detectability – or actually controllability and observability – conditions are satisfied:

rank(ctrb(A,B)), rank(obsv(A,Q))(7, 7)The conditions are obviously satisfied, hence a unique stabilizing positive definite solution to DARE exists. We can compute it using a dedicated solver and we can form the matrix of state feedback gains:

S = dare(A,B,Q,R)

K = (R+B'*S*B)\B'*S*A2×7 Matrix{Float64}:

0.32331 -2.90175 -0.73217 … 0.030565 0.00361445 -0.0242721

-1.32507 -0.173493 -0.0398993 0.00352081 0.00384607 -0.0187199Alternatively, we could use the higher-level lqr or dlqr functions (K = lqr(Gd,Q,R), or K = dlqr(A,B,Q,R)). Finally we can use the computed gains to construct the controller and simulate and plot a response of the system to nonzero initial conditions:

u(x,t) = -K*x # Control law

t=0:Ts:10.0

x0 = [1/10, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0]

y, t, x, uout = lsim(Gd,u,t,x0=x0)

using Plots, LaTeXStrings

p1 = plot(t,uout', label=[L"u_\mathrm{a} \mathrm{(rad)}" L"u_\mathrm{r} \mathrm{(rad)}"], xlabel="Time (s)", ylabel="Controls",markershape=:circle,markersize=1,linetype=:steppost)

p2 = plot(t,x[1:4,:]', label=[L"\beta \mathrm{(rad)}" L"\phi \mathrm{(rad)}" L"p \mathrm{(rad/s)}" L"r \mathrm{(rad/s)}" L"\delta_a" L"\delta_r" L"r_w \mathrm{(deg/s)}"], xlabel="Time (s)", ylabel="States",markershape=:circle,markersize=1,linetype=:steppost)

p3 = plot(t,y', label=[L"r_\mathrm{w} \mathrm{(deg/s)}" L"p \mathrm{(deg/s)}" L"\beta \mathrm{(deg)}" L"\phi \mathrm{(deg)}"], xlabel="Time (s)", ylabel="Outputs",markershape=:circle,markersize=1,linetype=:steppost)

plot(p1,p2,p3,layout=(3,1))