Overview of continuous-time optimal control

Through this chapter we are entering into the realm of continuous-time optimal control – we are going to consider dynamical systems that evolve in continuous time, and we are going to search for control that also evolves in continuous time.

Sometimes (and actually very often) we can encounter the terms continuous systems and continuous control. We find the terminology rather unfortunate because it is not clear what the adjective continuous refers to. For example, it might (incorrectly) suggest that the control is a continuous function of time (or state), when we only mean that it is the time that evolves continuously; the control can be discontinuous as a function of time and/or state. That is why in our course we prefer the more explicit term continuous-time instead of just continuous.

Continuous-time optimal control problem

We start by considering a nonlinear continuous-time system modelled by the state equation \dot{\bm{x}}(t) = \mathbf f(\bm x(t),\bm u(t), t), where

- \bm x(t) \in \mathbb R^n is the state vector at the continuous time t\in \mathbb R,

- \bm u(t) \in \mathbb R^m is the control vector at the continuous time t,

- \mathbf f: \mathbb{R}^n \times \mathbb{R}^m \times \mathbb R \to \mathbb{R}^n is the state transition function (in general not only nonlinear but also time-varying).

A general nonlinear continuous-time optimal control problem (OCP) is then formulated as \begin{aligned} \operatorname*{minimize}_{\bm u(\cdot), \bm x(\cdot)}&\quad \left(\phi(\bm x(t_\mathrm{f}),t_\mathrm{f}) + \int_{t_\mathrm{i}}^{t_\mathrm{f}} L(\bm x(t),\bm u(t),t) \; \mathrm{d}t \right)\\ \text{subject to} &\quad \dot {\bm{x}}(t) = \mathbf f(\bm x(t),\bm u(t), t),\quad t \in [t_\mathrm{i},t_\mathrm{f}],\\ &\quad \bm u(t) \in \mathcal U(t),\\ &\quad \bm x(t) \in \mathcal X(t), \end{aligned} where

- t_\mathrm{i} is the initial continuous time,

- t_\mathrm{f} is the final continuous time,

- \phi() is a terminal cost function that penalizes the state at the final time (and possibly the final time too if it is regarded as an optimization variable),

- L() is a running (also stage) cost function,

- and \mathcal U(t) and \mathcal X(t) are (possibly time-dependent) sets of feasible controls and states – these sets are typically expressed using equations and inequalities. Should they be constant (not changing in time), the notation is just \mathcal U and \mathcal X.

Oftentimes it is convenient to handle the constraints of the initial and final states separately: \begin{aligned} \operatorname*{minimize}_{\bm u(\cdot), \bm x(\cdot)}&\quad \left(\phi(\bm x(t_\mathrm{f}),t_\mathrm{f}) + \int_{t_\mathrm{i}}^{t_\mathrm{f}} L(\bm x(t),\bm u(t),t) \; \mathrm{d}t \right)\\ \text{subject to} &\quad \dot {\bm{x}}(t) = \mathbf f(\bm x(t),\bm u(t), t),\quad t \in [t_\mathrm{i},t_\mathrm{f}],\\ &\quad \bm u(t) \in \mathcal U(t),\\ &\quad \bm x(t) \in \mathcal X(t),\\ &\quad \bm x(t_\mathrm{i}) \in \mathcal X_\mathrm{init},\\ &\quad \bm x(t_\mathrm{f}) \in \mathcal X_\mathrm{final}. \end{aligned}

In particular, at the initial time just one particular state is often considered. At the final time, the state might be required to be equal to some given value, it might be required to be in some set defined through equations or inequalities, or it might be left unconstrained. Finally, the constraints on the control and states typically (but not always) come in the form of lower and upper bounds. The optimal control problem then specializes to \begin{aligned} \operatorname*{minimize}_{\bm u(\cdot), \bm x(\cdot)}&\quad \left(\phi(\bm x(t_\mathrm{f}),t_\mathrm{f}) + \int_{t_\mathrm{i}}^{t_\mathrm{f}} L(\bm x(t),\bm u(t),t) \; \mathrm{d}t \right)\\ \text{subject to} &\quad \dot {\bm{x}}(t) = \mathbf f(\bm x(t),\bm u(t)),\quad t \in [t_\mathrm{i},t_\mathrm{f}],\\ &\quad \bm u_{\min} \leq \bm u(t) \leq \bm u_{\max},\\ &\quad \bm x_{\min} \leq \bm x(t) \leq \bm x_{\max},\\ &\quad \bm x(t_\mathrm{i}) = \mathbf x^\text{init},\\ &\quad \left(\bm x(t_\mathrm{f}) = \mathbf x^\text{ref}, \; \text{or} \; \mathbf h_\text{final}(\bm x(t_\mathrm{f})) = \mathbf 0, \text{or} \; \mathbf g_\text{final}(\bm x(t_\mathrm{f})) \leq \mathbf 0\right), \end{aligned} where

- the inequalities should be interpreted componentwise,

- \bm u_{\min} and \bm u_{\max} are lower and upper bounds on the control, respectively,

- \bm x_{\min} and \bm x_{\max} are lower and upper bounds on the state, respectively,

- \mathbf x^\text{init} is a fixed initial state,

- \mathbf x^\text{ref} is a required (reference) final state,

- and the functions \mathbf g_\text{final}() and \mathbf h_\text{final}() can be used to define the constraint set for the final state.

The cost function in the above defined optimal control problem contains both the cost incurred at the final time and the cumulative cost (the integral of the running cost) incurred over the whole interval. An optimal control problem with this general cost function is called Bolza problem in the literature. If the cost function only penalizes the final state and the final time, the problem is called Mayer problem. If the cost function only penalizes the cumulative cost, the problem is called Lagrange problem.

Why continuous-time optimal control?

Why are we interested in continuous-time optimal control when at the end of the day most if not all controllers are implemented using computers and hence in discrete time? There are several reasons:

The theory for continuous-time optimal control is highly mature and represents a pinnacle of human ingenuity. It would be a pity to ignore it. It is also much richer than the theory for discrete-time optimal control. For example, when considering the time-optimal control, we can differentiate the cost function with respect to the final time because it is a continuous (real) variable.

Although the theoretical concepts needed for continuous-time optimal control are more advanced (integrals and derivatives instead of sums and differences, function spaces instead of spaces of sequences, calculus of variations instead of differential calculus), the results are often simpler than in the discrete-time case – the resulting formulas just look neater and more compact.

We will see later that methods for solving general continuous-time optimal control problems must use some kind of (temporal)discretization. Isn’t it then enough to study discretization and discrete-time optimal control separately? It will turn out that discretization can be regarded as a part of the solution process.

Approaches to continuous-time optimal control

There are essentially the same three approaches to continuous-time optimal control as we have seen when studying discrete-time optimal control:

- indirect approaches,

- direct approaches,

- dynamic programming.

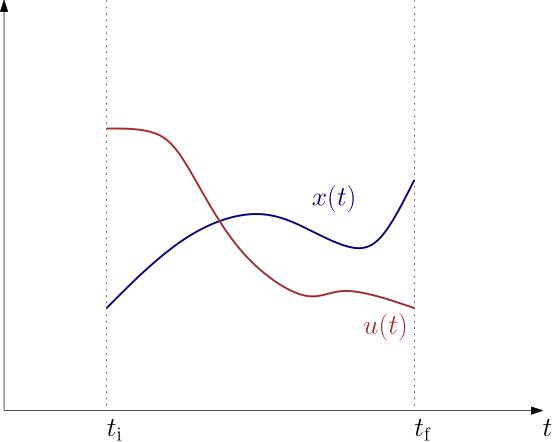

Unlike in the chapters on optimal control of discrete-time systems, here we start with the indirect approach. We would like to mimic the methodology we introduced for discrete-time system, but note that here we are not optimizing over n-tuples of real numbers (aka vectors or finite or even infinite sequences) but we are optimizing over functions (trajectories). Instances of such optimization “variables” are shown in Figure 2.

In order to be able to analyze such optimization problem, we need to introduce the framework of calculus of variations, which is what we do next.