Stability via common Lyapunov function

Having just recalled the stability analysis based on searching for a Lyapunov function, we now extend the analysis to hybrid systems, in particular, hybrid automata.

Hybrid system stability analysis via Lyapunov function

In contrast to continuous systems where Lyapunov functin should decrease along the state trajectory to certify asymptotic stability (or at least should not increase to certify Lyapunov stability), in hybrid systems the requirement can be relaxed a bit.

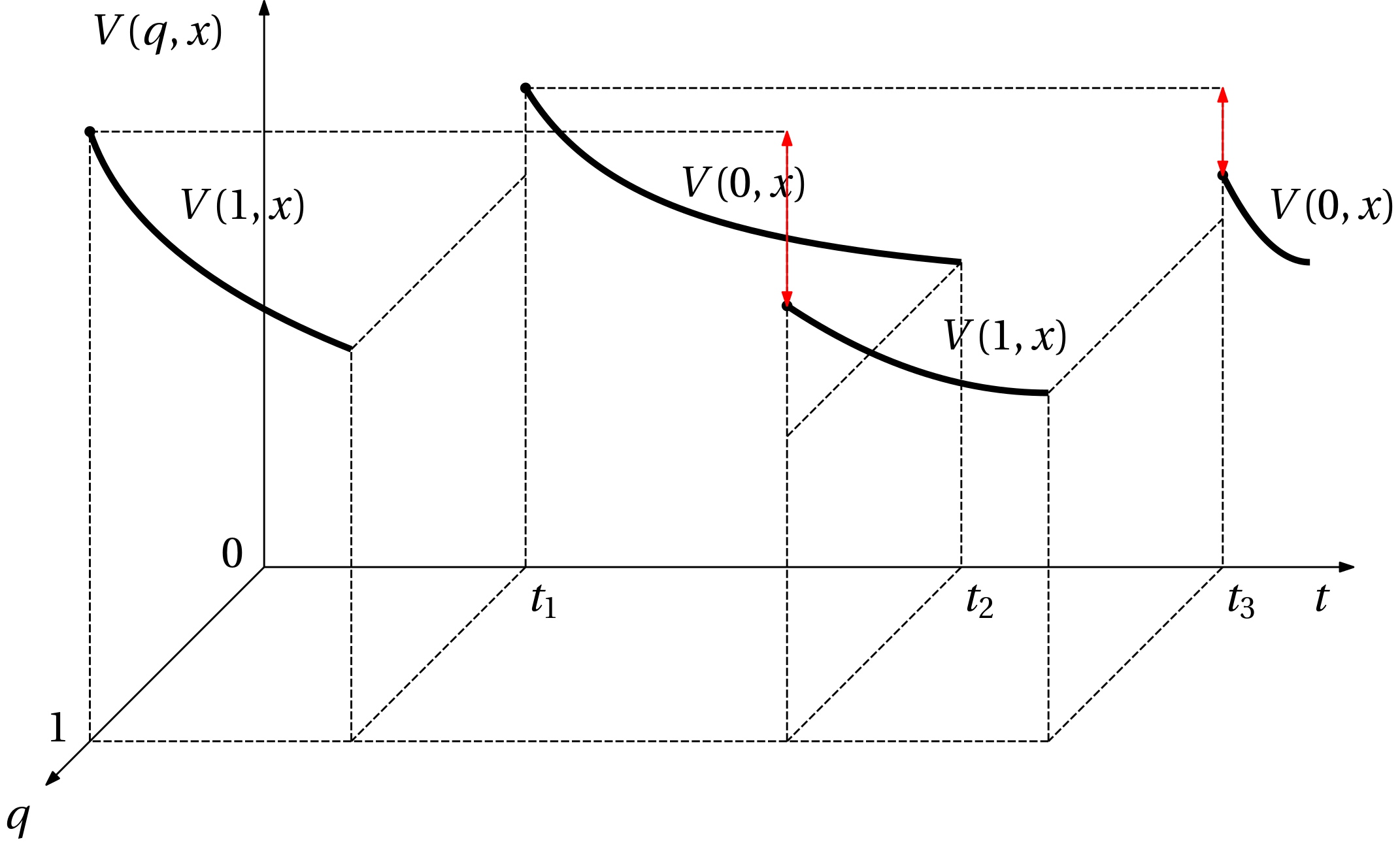

A Lyapunov function should still decrease along the continuous state trajectory while the system resides in a given discrete state (mode), but during the transition between the modes the function can be discontinuous, and can even increase. But then upon return to the same discrete state, the function should have lower value than it had last time it entered the state to certify asymptotic stability (or at least not larger for Lyapunov stability), see Fig. 1.

Formally, the function V(q,\bm x) has two variables q and \bm x, it is smooth in \bm x, and

V(q,\bm 0) = 0, \quad V(q,\bm x) > 0 \; \text{for all nonzero} \; \bm x \; \text{and for all nonzero} \; q,

\left(\nabla_x V(q,\bm x)\right)^\top \mathbf f(q,\bm x) < 0 \; \text{for all nonzero} \; \bm x \; \text{and for all nonzero} \; q,

and the discontinuities at transitions must satisfy the conditions sketched in Fig. 1. If Lyapunov stability is enough, the strict inequality can be relaxed to nonstrict.

Stricter condition on Lyapunov function

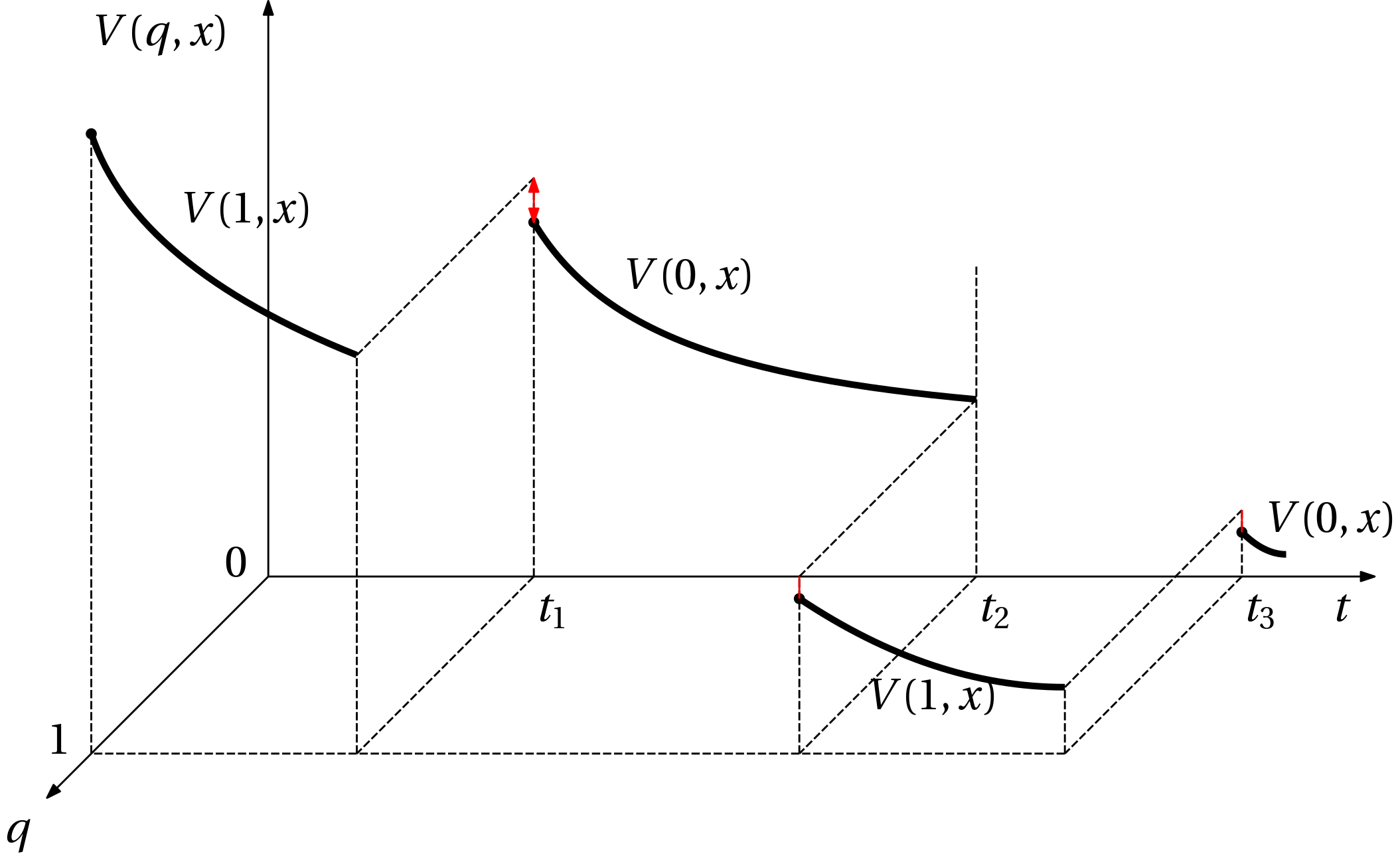

Verifying the properties just described is not easy. Perhaps the only way is to simulate the system, evaluate the function along the trajectory and check if the conditions are satisfied, which is hardly useful. A stricter condition is in Fig. 2. Here we require that during transitions to another mode, the fuction should not increase. Discontinuous reductions in value are allowed, but enforcing continuity introduced yet another simplification that can be plausible for analysis.

Further restricted set of candidate functions: common Lyapunov function (CLF)

In the above, we have considered a Lyapunov function V(q,\bm x) that is mode-dependent. But what if we could find a single Lyapunov function V(\bm x) that is common for all modes q? This would be a great simplification.

This, however, implies that at a given state \bm x, arbitrary transition to another mode q is possible. We add and adjective uniform the stabilty (either Lyapunov or asymptotic) to emphasize that the function is common for all modes.

In terminology of switched systems, we say that arbitrary switching is allowed. And staying in the domain of switched systems, the analysis can be interpreted within the framework of differential inclusions \dot{\bm x} \in \{f_1(\bm x), f_2(\bm x),\ldots,f_m(\bm x)\}.

(Global) uniform asymptotic stability

Having agreed that we are now searching for a single function V(\bm x), the function must satisfy \boxed{\kappa_1(\|\bm x\|) \leq V(\bm x) \leq \kappa_2(\|\bm x\|),} where \kappa_1(\cdot), \kappa_2(\cdot) are class \mathcal{K} comparison functions, and \kappa_1(\cdot)\in\mathcal{K}_\infty if global asymptotic stability is needed, and \boxed{\left(\nabla V(\bm x)\right)^\top \mathbf f_q(\bm x) \leq -\rho(\|\bm x\|),\quad q\in\mathcal{Q},} where \rho(\cdot) is a positive definite continuous function, zero at the origin. If all these are satisfied, the system is (globally) uniformly asymptotically stable (GUAS).

Similarly as we did in continuous systems, we must ask if stability implies existence of a common Lyapunov function. An affirmative answer comes in the form of a converse theorem for global uniform asymptotic stability (GUAS).

This is great, a CLF exists for a GUAS system, but how do we find it? We must restrict the set of candidate functions and then search within the set. Obviously, if we fail to find a function in the set, we must extend the set and search again…

Common quadratic Lyapunov function (CQLF)

An immediate restriction of a set of Lyapunov functions is to quadratic functions V(\bm x) = \bm x^\top \mathbf P \bm x, where \mathbf P=\mathbf P^\top \succ 0.

This restriction is also quite natural because for linear systems, it is known that we do not have to consider anything more complicated than quadratic functions. This does not hold in general for nonlinear and hybrid systems. But it is a good start. If we succeed in finding a quadratic Lyapunov function, we can be sure that the system is stable.

Here we start by considering a hybrid automaton for which at each mode the dynamics is linear. We consider r continuous-time LTI systems parameterized by the system matrices \mathbf A_i for i=1,\ldots, r as \dot{\bm x} = \mathbf A_i \bm x(t).

Time derivatives of V(\bm x) along the trajectory of the i-th system \nabla V(\bm x)^\top \left.\frac{\mathrm d \bm x}{\mathrm d t}\right|_{\dot{\bm x} = \mathbf A_i \bm x} = \bm x^\top(\mathbf A_i^\top \mathbf P + \mathbf P\mathbf A_i)\bm x,

which, upon introduction of new matrix variables \mathbf Q_i=\mathbf Q_i^\top given by

\mathbf A_i^\top \mathbf P + \mathbf P\mathbf A_i = \mathbf Q_i,\qquad i=1,\ldots, r

yields

\dot V(\bm x) = \bm x^\top \mathbf Q_i\bm x,

from which it follows that \mathbf Q_i (for all i=1,\ldots,r) must satisfy

\bm x^\top \mathbf Q_i \bm x \leq 0,\qquad i=1,\ldots, r

for (Lyapunov) stability and

\bm x^\top \mathbf Q_i \bm x < 0,\qquad i=1,\ldots, r

for asymptotic stability.

As a matter of fact, we could proceeded without introducing new variables \mathbf Q_i and just write the conditions directly in terms of \mathbf A_i and \mathbf P

\bm x^\top (\mathbf A_i^\top \mathbf P + \mathbf P\mathbf A_i) \bm x \leq 0,\qquad i=1,\ldots, r

for (Lyapunov) stability and

\bm x^\top (\mathbf A_i^\top \mathbf P + \mathbf P\mathbf A_i) \bm x < 0,\qquad i=1,\ldots, r

for asymptotic stability.

Linear matrix inequality (LMI)

The conditions of quadratic stability that we have just derived are conditions on functions. However, in this case of a quadratic Lyapunov function and linear systems, the condition can also be written directly in terms of matrices. For that we use the concept of a linear matrix inequality (LMI).

Recall that a linear inequality is an inequality of the form \underbrace{a_0 a_1x_1 + a_2x_2 + \ldots + a_rx_r}_{a(\bm x)} > 0.

We could perhaps argue that as the function a(x) is an affine and not linear, the inequality should be called an affine inequality. However, the term linear inequality is well established in the literature. It can be perhaps justified by moving the constant term to the right-hand side, in which case we have a linear function on the left and a constant term on the right, which is the same situation as in the \mathbf A\bm x=\mathbf b equation, which we call linear without hesitation.

A linear matrix inequality is a generalization of this concept where the coefficients are matrices.

\underbrace{\mathbf A_0 + \mathbf A_1\bm x_1 + \mathbf A_2\bm x_2 + \ldots + \mathbf A_r\bm x_r}_{\mathbf A(\bm x)} \succ 0.

Besides having matrix coefficients, another crucial difference is the meaning of the inequality. In this case it should not be interpreted component-wise but rather \mathbf A(\bm x)\succ 0 means that the matrix \mathbf A(\bm x) is positive definite.

Alternatively, the individual scalar variables can be assembled into matrices, in which case the LMI can have the form with matrix variables \mathbf F(\bm X) = \mathbf F_0 + \mathbf F_1\bm X\mathbf G_1 + \mathbf F_2\bm X\mathbf G_2 + \ldots + \mathbf F_k\bm X\mathbf G_k \succ 0, but the meaning of the inequality remains the same.

The use of LMIs is widespread in control theory. Here we formulate the LMI feasibility problem: does \bm X=\bm X^\top exist such that the LMI \mathbf F(\bm X)\succ 0 is satisfied?

CQLF as an LMI

Having formulated the problem of asymptotic stability using functions, we now rewrite it using matrices as an LMI: \begin{aligned} \mathbf P &\succ 0,\\ \mathbf A_1^\top \mathbf P + \mathbf P\mathbf A_1 &\prec 0,\\ \mathbf A_2^\top \mathbf P + \mathbf P\mathbf A_2 &\prec 0,\\ & \vdots \\ \mathbf A_r^\top \mathbf P + \mathbf P\mathbf A_r &\prec 0. \end{aligned}

Solving in Matlab using YALMIP or CVX

Most numerical solvers for semidefinite programs (SDP) can only handle nonstrict inequalities. We can enforce strict inequality by introducing some small \epsilon>0: \begin{aligned} \mathbf P &\succeq \epsilon I,\\ \mathbf A_1^\top \mathbf P + \mathbf P\mathbf A_1 &\preceq \epsilon I,\\ \mathbf A_2^\top \mathbf P + \mathbf P\mathbf A_2 &\preceq \epsilon \mathbf I,\\ & \vdots \\ \mathbf A_r^\top \mathbf P + \mathbf P\mathbf A_r &\preceq \epsilon \mathbf I. \end{aligned}

For LMIs with no affine term, we can multiply them (by 1/\epsilon) to get the identity matrix on the right-hand side: \begin{aligned} \mathbf P &\succeq \mathbf I,\\ \mathbf A_1^\top \mathbf P + \mathbf P\mathbf A_1 &\preceq \mathbf I,\\ \mathbf A_2^\top \mathbf P + \mathbf P\mathbf A_2 &\preceq \mathbf I,\\ & \vdots \\ \mathbf A_r^\top \mathbf P + \mathbf P\mathbf A_r &\preceq \mathbf I. \end{aligned}

Solution set of an LMI is convex

An important property of a solution set of an LMI is that it is convex. Indeed, it is a crucial property. An implication is that if a solution \mathbf P exists for the r inequalities, then it is also a solution for an inequality given by and convex combination of the matrices \mathbf A_i. That is, if a solution \mathbf P=\mathbf P^\top \succ 0 exists such that \begin{aligned} \mathbf A_1^\top \mathbf P + \mathbf P\mathbf A_1 &\prec 0,\\ \mathbf A_2^\top \mathbf P + \mathbf P\mathbf A_2 &\prec 0,\\ & \vdots \\ \mathbf A_r^\top \mathbf P + \mathbf P\mathbf A_r &\prec 0, \end{aligned} then \mathbf P also solves the convex combination \left(\sum_{i=1}^r\alpha_i \mathbf A_i\right)^\top \mathbf P + \mathbf P\left(\sum_{i=1}^r\alpha_i \mathbf A_i\right) \prec 0, where \alpha_1, \alpha_2, \ldots, \alpha_r \geq 0 and \sum_i \alpha_i = 1.

This leads to an interesting interpretation of the requirement of (asymptotic) stability in presence of arbitrary switching – every convex combination of the systems is stable. While we do not exploit it in our course, note that it can be used in robust control design – an uncertain system is modelled by a convex combination of some vertex models. When designing a single (robust) controller, it is sufficient to guarantee stability of the vertex models using a single Lyapunov function, and the convexity property ensures that the controller is also robust with respect to the uncertain system. A powerful property! On the other hand, rather too strong because it allows arbitrarily fast changes of parameters.

Note that we can use the convexity property when formulating this problem equivalently as the problem of stability analysis of the linear differential inclusion \dot{\bm x} \in \mathcal{F}(\bm x), where \mathcal{F}(\bm x) = \overline{\operatorname{co}}\{\mathbf A_1\bm x, \mathbf A_2\bm x, \ldots, \mathbf A_r\bm x\}.

What if quadratic LF is not enough?

So far we considered quadratic Lyapunov functions – and it may be useful to display their prescription explicitly in the scalar form \begin{aligned} V(\bm x) &= \bm x^\top \mathbf P \bm x\\ &= \begin{bmatrix}x_1 & x_2\end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} p_{11} & p_{12}\\ p_{12} & p_{22}\end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix}x_1\\ x_2\end{bmatrix}\\ &= p_{11}x_1^2 + 2p_{12}x_1x_2 + p_{22}x_2 \end{aligned} to show that, indeed, a quadratic Lyapunov function is a (multivariate) quadratic polynomial.

Now, if quadratic polynomials are not enough, it is natural to consider polynomials of a higher degree. The crucial question is, however: how do we enforce positive definiteness?

Positive/nonnegative polynomials

The question that we ask is this: is the polynomial p(\bm x), \; \bm x\in \mathbb R^n, positive (or at least nonnegative) on the whole \mathbb R^n? That is, we ask if p(\bm x) > 0,\quad (\text{or}\quad p(\bm x) \geq 0)\; \forall \bm x\in\mathbb R^n.

Example 1 Consider the polynomial p(\bm x)= 2x_1^4 + 2x_1^3x_2 - x_1^2x_2^2 + 5x_2^4. Is it nonnegative for all x_1\in\mathbb R, x_2\in\mathbb R?

Additionally, \bm x can be restricted to some \mathcal X\sub \mathbb R^n and we ask if

p(\bm x) \geq 0 \;\forall\; \bm x\in \mathcal X.

Once we started working with polynomials, semialgebraic sets \mathcal X are often considered, asthese are defined by polynomial inequalities such as g_j(\bm x) \geq 0, \; j=1,\ldots, m.

But this we are only going to need in the next chapter, when we consider Multiple Lyapunov Functions (MLF) approach to stability analysis.

How can we check positivity/nonnegativity of polynomials?

Gridding is certainly not the way to go – we need conditions on the coefficients of the polynomial so that we can do some optimization later.

Example 2 Consider a univariate polynomial p(x) = x^4 - 4x^3 + 13x^2 - 18x + 17. Does it hold that p(x)\geq 0 \; \forall x\in \mathbb R? Without plotting (hence gridding) we can hardly say. But what if we learn that the polynomial can be written as p = (x-1)^2 + (x^2 - 2x + 4)^2

Obviously, whatever the two squared polynomials are, after squaring they become nonnegative. And summing nonnegative numbers yields a nonnegative result. Let’s generalize this.

Sum of squares (SOS) polynomials

If we can express the polynomial as a sum of squares (SOS) of some other polynomials, the original polynomial is nonnegative, that is, \boxed{p(\bm x) = \sum_{i=1}^k p_i(\bm x)^2\; \Rightarrow \; p(\bm x) \geq 0,\; \forall \bm x\in \mathbb R^n.}

The converse does not hold in general – not every nonnegative polynomial is SOS! There are only three cases, for which SOS is a necessary and sufficient condition of nonnegativeness:

- n=1: univariate polynomials. The degree (the highest power) d can be arbitrarily high (but even, obviously),

- d = 2 and n is arbitrary: multivariate polynomials of degree two (note that for p(\bm x) = x_1^2 + x_1x_2^2 the degree d=3).

- n=2 and d = 4: bivariate polynomials of degree 4 (at maximum).

For all other cases all we can say is that p(\bm x)\, \text{is}\, \mathrm{SOS} \Rightarrow p(\bm x)\geq 0\, \forall \bm x\in \mathbb R^n.

Hilbert conjectured in 1900 in the 17th problem that every nonnegative polynomial can be written as a sum of squares of rational functions. This was later proved correct. It turns out, that this fact is not as useful as the SOS using polynomials because of impossibility to state apriori the bounds on the degrees of the polynomials defining those rational functions.

How to get an SOS representation of a polynomial (or prove that none exist)?

Univariate case

Back to the univariate example first. And we do it through an example.

Example 3 We consider the polynomial in the Example 2. One of the two squared polynomials is x^2 - 2x + 4. We can write it as x^2 - 2x + 4 = \underbrace{\begin{bmatrix}4 & -2 & 1\end{bmatrix}}_{\bm v^\top} \underbrace{\begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ x \\ x^2\end{bmatrix}}_{\bm z}.

Then the squared polynomial can be written as (x^2 - 2x + 4)^2 = \bm z^\top \bm v \bm v^\top \bm z.

Note that the the product \bm v \bm v^\top is a positive semidefinite matrix of rank one.

We can similarly express the second squared polynomial x-1 = \underbrace{\begin{bmatrix} -1 & 1 & 0\end{bmatrix}}_{\bm v^\top} \underbrace{\begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ x \\ x^2\end{bmatrix}}_{\bm z} and then (x - 1)^2 = \bm z^\top \begin{bmatrix} -1 \\ 1 \\ 0\end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} -1 & 1 & 0\end{bmatrix} \bm z.

Summing the two squares we get the original polynomial. But while doing this, we can sum the two rank-one matrices. \begin{aligned} p(x) &= x^4 - 4x^3 + 13x^2 - 18x + 17\\ &= \begin{bmatrix} 1 & x & x^2\end{bmatrix} \bm P \begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ x \\ x^2\end{bmatrix} \end{aligned}, where \bm P\succeq 0 is \bm P = \underbrace{\begin{bmatrix} 4 \\ -2 \\ 1\end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} 4 & -2 & 1\end{bmatrix}}_{\mathbf P_1} + \underbrace{\begin{bmatrix} -1 \\ 1 \\ 0\end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} -1 & 1 & 0\end{bmatrix}}_{\mathbf P_2}

The matrix that defines the quadratic form is positive semidefinite and of rank 2. Indeed, the rank of the matrix is given by the number of squared terms in the SOS decomposition.

Multivariate case

In a general multivariate case we can proceed similarly. Just form the vector \bm z from all possible monomials: \bm z = \begin{bmatrix}1 \\ x_1 \\ x_2 \\ \\ \vdots \\ x_n\\ x_1^2 \\ x_1 x_2 \\ \vdots \\ x_n^2\\\vdots \\x_1x_2\ldots x_n^{2}\\ \vdots \\ x_n^d \end{bmatrix}

But how to determine the coefficients of the matrix? We again show it by means of an example.

We consider the polynomial p(x_1,x_2)=2x_1^4 +2x_1^3x_2 − x_1^2x_2^2 +5x_2^4. We define the vector \bm z as \bm z = \begin{bmatrix} x_1^2 \\ x_1x_2 \\ x_2^2\end{bmatrix}.

Note that we could also write it fully as \bm z = \begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ x_1\\ x_2\\ x_1^2 \\ x_1x_2 \\ x_2^2\end{bmatrix}, but we can see that the first three terms are not going to be needed. If you still cannot see it, feel free to continue with the full version of \bm z, no problem.

Then the polynomial can be written as p(x_1,x_2)=\begin{bmatrix} x_1^2 \\ x_1x_2 \\ x_2^2\end{bmatrix}^\top \begin{bmatrix} p_{11} & p_{12} & p_{13}\\ p_{12} & p_{22} & p_{23}\\p_{13} & p_{23} & p_{33}\end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} x_1^2 \\ x_1x_2 \\ x_2^2\end{bmatrix}.

After multiplying the producs out, we get \begin{aligned} p(x_1,x_2)&={\color{blue}p_{11}}x_1^4 + {\color{blue}p_{33}}x_2^4 \\ &\quad + {\color{blue}2p_{12}}x_1^3x_2 + {\color{blue}2p_{23}}x_1x_2^3\\ &\quad + {\color{blue}(2p_{13} + p_{22})}x_1^2x_2^2 \end{aligned}

There are now 5 coefficients in the above polynomial (they are highlighted in blue). Equating them to some particular values gives 5 equations.

But the matrix \mathbf P is parameterized by 6 coefficients. Hence we need one more equation. The sixth is the LMI condition \mathbf P\succeq 0.

Searching for a SOS polynomial Lyapunov function

We can now formulate the search for a nonnegative polynomial function V(\bm x) as a search within the set of SOS polynomials of a prescribed degree d.

However, for a Lyapunov function, we need positiveness (actually positive definiteness), not just nonnegativeness.Therefore, instead of V(\bm x) \; \text{is SOS}, we are going to impose the condition \boxed{ V(\bm x) - \phi(\bm x) \; \text{is SOS},} where \phi(\bm x) = \gamma \sum_{i=1}^n\sum_{j=1}^{d} x_i^{2j} for some (typically very small) \gamma > 0. This is pretty much the same trick that we used in the LMI formulation when we needed enforce strict inequalities.

What remains to complete the conditions for Lyapunov stability, is to express the requirement that the time derivative of V(\bm x) is nonpositive. This can also be done by requiring that minus the time derivative of the polynomial Lyapunov function, which is a polynomial too, is SOS too.

\boxed {-\nabla V(\bm x)^\top \mathbf f(\bm x)\; \text{is SOS}.}

If asymptotic stability is required instead of just Lyapunov one, the condition is that the time derivative is strictly negative, that is, we can require that \boxed {-\nabla V(\bm x)^\top \mathbf f(\bm x) - \phi(\bm x)\; \text{is SOS}.}

Searching for a SOS polynomial common Lyapunov function

Back to hybrid systems. For Lyapunov stability, the problem is to find V(\bm x) such that

\boxed{ \begin{aligned} V(\bm x) - \phi(\bm x) \; &\text{is SOS},\\ -\nabla V(\bm x)^\top \mathbf f_1(\bm x)\; &\text{is SOS},\\ -\nabla V(\bm x)^\top \mathbf f_2(\bm x)\; &\text{is SOS},\\ \vdots\\ -\nabla V(\bm x)^\top \mathbf f_r(\bm x)\; &\text{is SOS}, \end{aligned} } while for asymptotic stability, the conditions are \boxed{ \begin{aligned} V(\bm x) - \phi(\bm x) \; &\text{is SOS},\\ -\nabla V(\bm x)^\top \mathbf f_1(\bm x) - \phi(\bm x)\; &\text{is SOS},\\ -\nabla V(\bm x)^\top \mathbf f_2(\bm x) - \phi(\bm x)\; &\text{is SOS},\\ \vdots\\ -\nabla V(\bm x)^\top \mathbf f_r(\bm x) - \phi(\bm x)\; &\text{is SOS}. \end{aligned} }