Max-plus linear (MPL) systems

We start with an example of a discrete-event systems modelled using (max,+) algebra.

Example 1 (Production system)

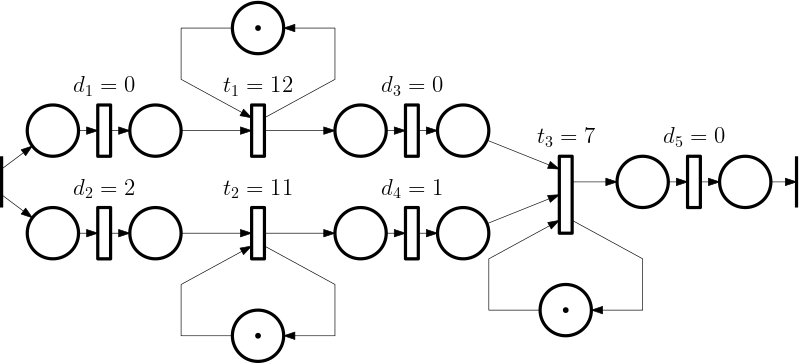

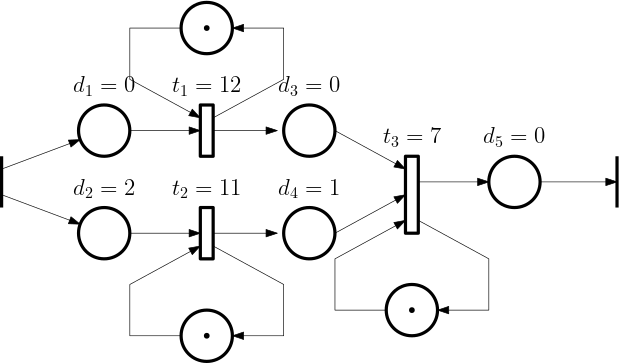

- There are 3 production units: P_1, P_2, P_3.

- The unit P_3 waits for the outputs from the units P_1 and P_2.

- Each unit introduces a processing delay: v_1 = 12, v_2 = 11, v_3 = 7, respectively.

- There are also transportation delays: d_2 = 2 from the entry to P_2, and d_4 = 1 from P_2 to P_3. All the other transportation delays are negligible.

Timed Petri net (event graph) for the example is in Fig. 1 below.

The Petri net can be made more compact by associating the delays also with the places, as in Fig. 2 below.

With the outputs from the three transitions (the rectangles) after the kth event labelled by x_{1,k}, x_{2,k}, and x_{3,k}, the state equations are \begin{aligned} x_{1,k} &= \max\{x_{1,k-1} + 12, u_k + 0\}\\ x_{2,k} &= \max\{x_{2,k-1} + 11, u_k + 2\}\\ x_{3,k} &= \max\{x_{3,k-1} + 7, x_{1,k} +12 + 0, x_{2,k} + 11 + 1\}\\ &= \max\{x_{3,k-1} + 7, \max\{x_{1,k-1} + 12, u_k\} +12, \\ &\qquad \max\{x_{2,k-1} + 11, u_k+2\} + 12\}\\ &= \max\{x_{3,k-1} + 7, x_{1,k-1} + 24, x_{2,k-1} + 23, \\ &\qquad\qquad u_k+14\}\\ y_k &= x_{3,k} + 7 \end{aligned}

The state equations can be rewritten in the (max,+) algebra \begin{aligned} \begin{bmatrix} x_{1,k} \\ x_{2,k} \\ x_{3,k} \end{bmatrix} &= \begin{bmatrix} 12 & \varepsilon & \varepsilon\\ \varepsilon & 11 & \varepsilon\\ 24 & 23 & 7 \end{bmatrix} \otimes \begin{bmatrix} x_{1,k-1} \\ x_{2,k-1} \\ x_{3,k-1} \end{bmatrix} \oplus \begin{bmatrix} 0 \\ 2 \\ 14 \end{bmatrix} \otimes u_k\\ y_k &= \begin{bmatrix} \varepsilon & \varepsilon & 7 \end{bmatrix} \otimes x_k \end{aligned}

Model of an event graph as a Max-plus linear (MPL) state-space system

Generalizing what we have seen in the previous example, we can write the MPL state-space system (actually a model) as \boxed{ \begin{aligned} x(k) &= A\otimes x(k-1) \oplus B\otimes u(k),\\ y(k) &= C\otimes x(k), \end{aligned}} \tag{1}

where A, B, and C are matrices of appropriate dimensions. or, equivalently (after relabelling)

\begin{aligned}

x(k+1) &= A\otimes x(k) \oplus B\otimes u(k),\\

y(k) &= C\otimes x(k),

\end{aligned}

which mimics the conventional state-space system

\begin{aligned}

x(k+1) &= A x(k) + Bu(k),\\

y(k) &= Cx(k).

\end{aligned}

We already know this from the example, but we need to emphasize it here again: the role of the variables u(k), x(k), y(k) is that they are event times. Namely the times of

- arrivals of inputs,

- beginning of processing

- finishing of processing,

respectively.

The independent variable k is now a counter of the events.

State response of an MPL system

In order to simulate an MPL system, we can now find use of the definitions of the basic operations in (max,+) algebra that we studied previously. Note that \begin{aligned} x_1 &= A\otimes x_0 \oplus B\otimes u_1\\ x_2 &= A\otimes x_1 \oplus B\otimes u_2\\ &= A\otimes (A\otimes x_0 \oplus B\otimes u_1) \oplus B\otimes u_2\\ &= A^{\otimes^2}\otimes x_0 \oplus A\otimes B\otimes u_1 \oplus B\otimes u_2\\ &\vdots \end{aligned} which can be generalized to \boxed{ x_k = A^{\otimes^k}\otimes x_0 \oplus \bigoplus_{i=1}^k A^{\otimes^{k-i}} \otimes B\otimes u_i.} \tag{2}

The response of a linear time-invariant (LTI) system described by a (vector) state equation x(k+1) = Ax(k) + Bu(k) is x_{k} = A^k x_0 + \sum_{i=0}^{k-1} A^{k-1-i}Bu_i.

Note how the lower and upper bounds for the summation are shifted by 1 compared to the traditional convolution.

(max,+) linearity

We should emphasize that the linearity exhibited by the state equation Eq. 1 and the convolution Eq. 2 must only be understood in the (max,+) sense.

Indeed, if we consider two input sequences u_1= \{u_{1,1},u_{1,2},\ldots\} and u_2= \{u_{2,1},u_{2,2},\ldots\}, a (max,+)-linear combination \alpha \otimes u_1 \oplus \beta \otimes u_2 of the two inputs yields the same (max,+)-linear combination of the outputs y_1 and y_2.

Input-output response of an MPL system

We can also eliminate the state variables from the model and aim at finding the relation between the input and output sequences U = \begin{bmatrix}u_1 \\ u_2 \\ \vdots \\ u_p\end{bmatrix}, \qquad Y = \begin{bmatrix}y_1 \\ y_2 \\ \vdots \\ y_p\end{bmatrix} in the form of \boxed {Y = G\otimes x_0 \oplus H\otimes U,} where H = \begin{bmatrix} C\otimes B & \varepsilon & \varepsilon & \ldots & \varepsilon\\ C\otimes A\otimes B & C\otimes B & \varepsilon & \ldots & \varepsilon\\ C\otimes A^{\otimes^2}\otimes B & C\otimes A\otimes B & C\otimes B & \ldots & \varepsilon\\ \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots\\ C\otimes A^{\otimes^{p-1}}\otimes B & C\otimes A^{\otimes^{p-2}}\otimes B & C\otimes A^{\otimes^{p-3}}\otimes B & \ldots & C\otimes B \end{bmatrix} and G = \begin{bmatrix} C \\ C\otimes A \\ C\otimes A^{\otimes^2} \\ \vdots \\ C\otimes A^{\otimes^{p-1}} \end{bmatrix}.

Example 2 (Production system) We consider again the production system in Example 1. On the time horizon of 4, and assuming zero initial state, the input-output model is paramaterized by Y = \begin{bmatrix}y_1 & y_2 & y_3 & y_4\end{bmatrix}^\top, \quad U = \begin{bmatrix}u_1 & u_2 & u_3 & u_4\end{bmatrix}^\top,

x_0 = \begin{bmatrix}\varepsilon & \varepsilon & \varepsilon\end{bmatrix}^\top,

H = \begin{bmatrix} 21 & \varepsilon & \varepsilon & \varepsilon\\ 32 & 21 & \varepsilon & \varepsilon\\ 43 & 32 & 21 & \varepsilon\\ 55 & 43 & 32 & 21 \end{bmatrix}.

Analysis of an irreducible MPL system

We now consider an autonomous MPL system x_{k+c} = A^{\otimes^{k+c}}\otimes x_0, for which we assume irreducibility of the matrix A.

We have learnt previously, that for large enough k and c, x_{k+c} = \lambda^{\otimes^c}\otimes A^{\otimes^{k}}\otimes x_0 = \lambda^{\otimes^c}\otimes x_k.

This can be interpreted in the standard algabra as x_{k+c} = c\lambda + x_k, from which it follows that x_{k+c}-x_k = c\lambda.

This is an insightful result. When the system under consideration is a production system, then once it reaches a cyclic behaviour, the average cycle is \lambda. The average production rate is then 1/\lambda.

Model Predictive Control (MPC) for MPL systems

Now we are finally ready to consider control problems form MPL systems. We will consider the MPC approach.

Cosf function for MPC

We consider the const function composed of two parts J = J_\mathrm{output} + \lambda J_\mathrm{input}.

At “time” k, with the prediction horizon N_\mathrm{p}, and with the number of outputs n_\mathrm{y}: J_\mathrm{output} = \sum_{j=0}^{N_\mathrm{p}-1}\sum_{i=1}^{n_\mathrm{y}} \max \{y_{i,k+j} - r_{i,k+j},0\}

This cost function penalizes tardiness (late delivery).

Is the lower value for j correct?

Alternative choice of the cost function is J_\mathrm{output} = \sum_{j=0}^{N_\mathrm{p}-1}\sum_{i=1}^{n_\mathrm{y}} \left|y_{i,k+j} - r_{i,k+j} \right |, which penalizes difference between the due and actual dates, or J_\mathrm{output} = \sum_{j=1}^{N_\mathrm{p}-1}\sum_{i=1}^{n_\mathrm{y}} \left |\Delta^2 y_{i,k+j}\right |, which balances the output rates.

The input cost can be set to J_\mathrm{input} = -\sum_{j=0}^{N_\mathrm{p}-1}\sum_{l=1}^{n_\mathrm{u}} u_{l,k+j}, which penalizes early feeding (favours just-in-time feeding). Note the minus sign.

Control horizon vs. prediction horizon

Assume constant feeding rate after the control horizon N_\mathrm{c} \Delta u_{k+j} = \Delta u_{k+N_\mathrm{c}-1},\qquad j=N_\mathrm{c},\ldots, N_\mathrm{p}-1 where \Delta u_k = u_k - u_{k-1}.

Alternatively, \Delta^2 u_{k+j} = 0,\qquad j=N_\mathrm{c},\ldots, N_\mathrm{p}-1 where \Delta^2 u_k = \Delta u_k - \Delta u_{k-1} = u_k - 2u_{k-1} + u_{k-2}.

Inequality constraints for MPC

There are several possibilities for the constraints in the MPC for MPL systems. For example, we can constrain the minimum and maximum separation of input and output events a_{k+j} \leq \Delta u_{k+j} \leq b_{k+j},\qquad j=0,1,\ldots,N_\mathrm{c}-1, c_{k+j} \leq \Delta y_{k+j} \leq d_{k+j},\qquad j=0,1,\ldots,N_\mathrm{p}-1.

We can also impose constraint on the maximum due dates for the output events y_{k+j} \leq r_{k+j},\qquad j=0,1,\ldots,N_\mathrm{p}-1.

We can also enforce the condition that the input and output events are consecutive \Delta u_{k+j} \geq 0, \qquad j=0,1,\ldots,N_\mathrm{c}-1.

MPC for MPL system leads to a nonlinear optimization problem

Our motivation for formulating the problems within the (max,+) algebra was to fake the reality a bit and pretend that the problem is linear. This allowed us to invoke many concepts that we are familiar with from linear systems theory. However, at the end of the day, when it comes to actually solving the problem, we must reveal the nonlinear nature of the problem.

When we consider the MPC for MPL systems, we are faced with a nonlinear optimization problem. We can use some general nonlinear solvers (fmincon, ipopt, …).

Alternatively, there is a dedicated framework for solving these problem. It is called Extended Linear Complementarity Problem (ELCP) and was developed by [1]. We will introduce the complementarity problem(s) later in a chapter dedicated to complementarity.

Yet another approach is through Mixed Integer (Linear) Programming (MILP).