Discrete-event systems

We have already mentioned that hybrid systems are composed of time-driven subsystems and event-driven subsystems. Assuming that the primary audience of this course are already familiar with the former (having been exposed to state equations and transfer function), here we are going to focus on the latter, also called discrete-event systems DES (or DEVS).

(Discrete) event

We need to start with the definition of an event. Sometimes an adjective discrete is added (to get discrete event), although it appears rather redundant.

The primary characteristic of an event is instantaneous occurence, that is, an event takes no time.

Within the context of systems, an event is associated with a change of state – transition of the system from one state to another. Between two events, the systems remains in the same state, it doesn’t evolve.

True, here we are making a reference to the concept of a state, which we haven’t defined yet. But we can surely rely on understanding this concept developed by studying the time-driven systems (modelled by state equations).

Although it is not instrumental in defining the event, the state space is frequently assumed discrete (even if infinite).

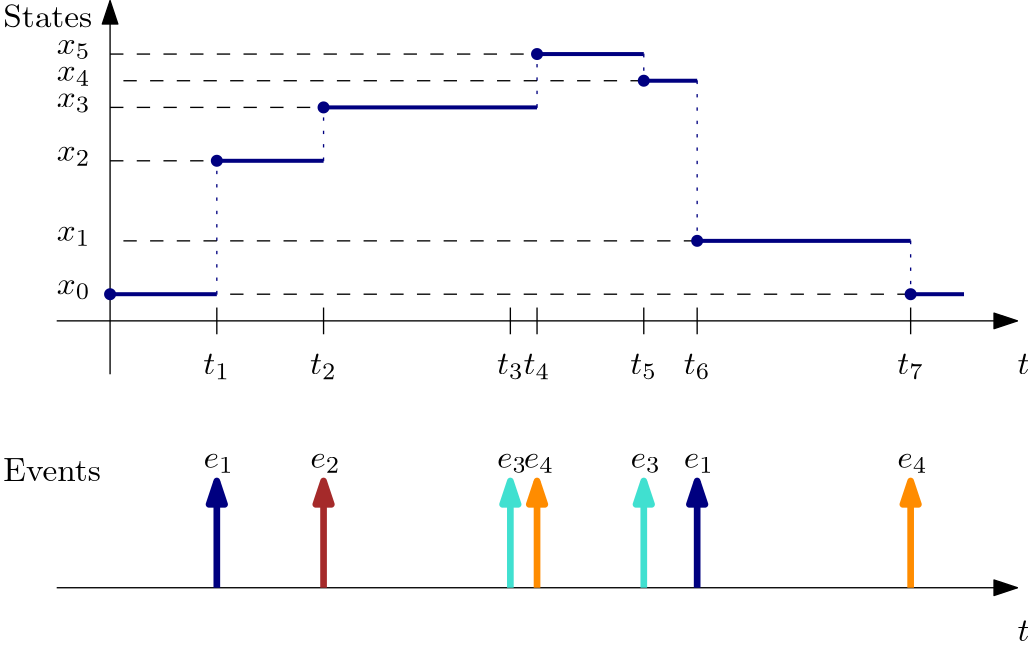

Example 1 (DES state trajectory) In the figure below we can see an example state trajectory of a discrete-event system corresponding to a particular sequence of events.

It is perhaps worth emphasizing that the state space is not necessarily equidistantly discretized.

Also note that for some events no transitions occur (e_3 at t_3).

The previous example also displays one particular annoying (and frequently occuring in literature) notational conflict. How shall we interpret the lower index? Sometimes it is used to refer to (discrete) time, and on some other occasions it can just refer to a particular element of a set. In other words, this is a notational clash between name of the variable and value of the variable. In the example above we obviously adopted the latter interpretation. But in other cases, we ourselves are prone to inconsistency. Just make sure you understand what the author means.

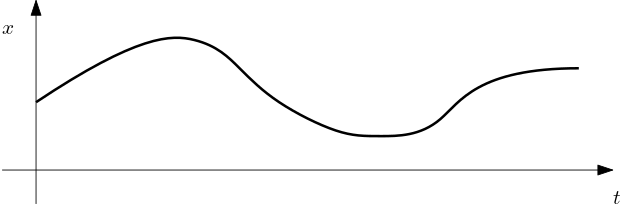

Example 2 (State trajectory of a continuous-time dynamical systems) Compare now the above example of a state trajectory in a DES with the example of a continuous-time state space system below, whose model could be \dot x(t) = f(x). In the latter, any change, however small, takes time. In other words, the system evolves continuously in time.

The set of states (aka state space) is \mathbb{R} (or a subset) in this case (in general \mathbb{R}^n or a subset).

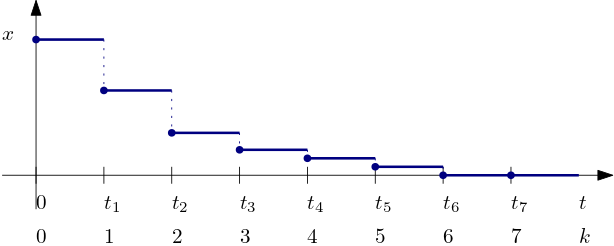

Example 3 (State trajectory of a time-discretized (aka sampled-data) system) As a yet another example of a state trajectory, consider the response of a discrete-time (actually time-discretized or also sampled-data system) system model by x_k = f(x_k) in the figure below. Although we could view the sampling instances as the events, these are given by time, hence the moments of transitions are predictable. Hence the system can still be viewed and analyzed as a time-driven and not event driven one.

When do events occur?

There are three major possibilities:

- when action is taken (button press, clutch released, …),

- spontaneously: well, this is just an “excuse” when the reason is difficult to trace down (computer failure, …),

- when some condition is met (water level is reached, …). This needs an introduction of a concept of a hybrid systems, wait for it.

Sequence of “time-stamped” events (aka timed trace)

The sequence of pairs (event, time) (e_1,t_1), (e_2,t_2), (e_3,t_3), \ldots

is sufficient to characterize an execution of a deterministic system, that is, a system with a unique initial state and a unique transitions at a given state and an event.

DES can be stochastic, but what exactly is stochastic then?

Stochasticity can be introduced in

- the event times (e.g. Poisson process),

- but also in the transitions (e.g. probabilistic automata, more on this later).

Sometimes time stamps not needed – the ordering of events is enough

The sequence of events (aka trace) e_1,e_2,e_3, \ldots can be enough for some analysis, in which only the order of the events is important.

Example 4 credit_card_swiped, pin_entered, amount_entered, money_withdrawn

Discrete-event systems are studied through their languages

When studying discrete-event systems, soon we are exposed to terminology from the formal language theory such as alphabet, word, and language. This must be rather confusing for most students (at least those with no education in computer science). In our course we are not going to use these terms actively (after all our only motivation for introducing the discipline of discrete-event systems is to take away just a few concepts that are useful in hybrid systems), but we want to sketch the motivation for their introduction to the discipline, which may make it easier for a student to skim through some materials on discrete-event systems.

We define at least those three terms that we have just mentioned. The definitions correspond to the everyday usage of these terms.

- Alphabet

- a set of symbols.

- Word (or string)

- a sequence of symbols from a finite alphabet.

- Language

- a set of words from the given alphabet.

Now, a symbol is used to label an event. Alphabet is then a set of possible events. A particular sequence of events (we also call it trace) is then represented by a word. Since we agreed that events are associated with state transitions of a corresponding system, a word represents a possible execution or run of a system. A set of all possible executions of a given system can then be formally viewed as language.

Indeed, all this is just a formalism, the agreement how to talk about things. We will see an example of this “jargon” in the next section when we introduce the concept of an automaton and some of its properties.

Modelling frameworks for DES (as used in our course)

These are the three frameworks that we are going to cover in our course. There may be some more, but these three are the major ones, and from these there is always some lesson to be learnt that we will find useful later when finally studying hybrid systems

- State automaton (pl. automata)

- Petri net

- (max,plus) algebra, MPL systems

While the first two frameworks are essentially equally powerful when it comes to modelling DES, the third one can be regarded as an algebraic framework for a subset of systems modelled by Petri nets.

We are going to cover all the three frameworks in this course as a prequel to hybrid systems.